4/. The Case for an Alternative English or French Origin Download

4.1/ Anglo-Saxon England: Potential Origins in Herts., Cambs., or East Anglian or Saxon counties.

[Vortigern's Treaty 450AD](Wikipedia)

King Harold Godwinson'1022-1066

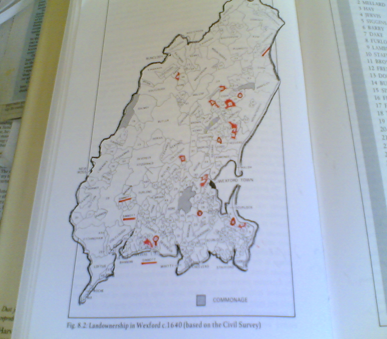

Selection of Sennett Estates' 1641Ch.5.1/5.6

4.1a/ Anglo-Saxon case for Sennett Origin, Domesday Book, possible case of spelling Convergence

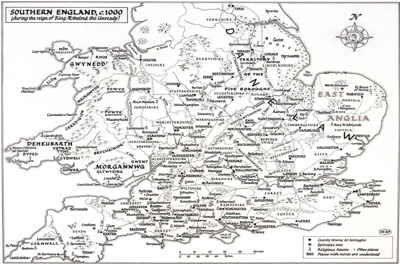

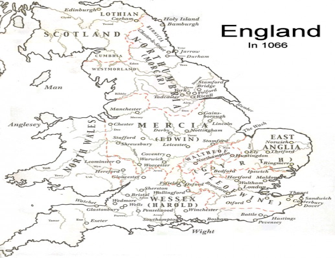

It must be said that notionally, while this second possibility of an Anglo-Saxon origin of the Sennett surname is feasible and underwritten by some evidence, it must remain currently only a possibility. It awaits some real and prospective but unknown genetic proof. It is inchoate. There is no Y-DNA evidence to date of such a distinctive and separate genetically-confirmed Anglo-Saxon source, one that has been associated with the modern usage of the Sennett surname and its many variants. There appears to have been no clustering within the England of ancient times of an Anglo-Saxon 'Sennett' such as we might know it today. The further back in history one goes, the less certain one can be as to how the name may have been spelt or represented in documentary form of the time. There remains nevertheless a strongly held belief that the likely place of emergence of a primal Sennett was in either of Cambridgeshire or Hertfordshire, and if not so, otherwise an early origin within the wider old East Anglian or Saxon Kingdoms of Mercia, Wessex, Sussex, Essex and Kent.

England became politically unified during the middle of the 10th Century, a time between the reigns of King Athelstan who claimed the throne from 926, and 'Ethelred the Unready' who died in 1016. There does seem to have been in the Anglo-Saxon England of this time a certain disparate occurrence of the vernacular name "Sigenõð" or "Sigenõth" as expressed in Olde English and then later Middle English speech. The name would take the spelling of "Sinod" in the documented Latin form. The documented Anglo-Saxon representation did not actually occur on the record in this form and spelling until late in the 11th Century. The Anglo-Saxon name has often been translated into modern English as meaning 'Victory Bold', alternatively 'Victory Brave'. These sample references to a 'Sennett' of this slightly later period are offered in the table below.

The Latin documented format of the name is taken to be Sinod. Given that the contemporary vernacular speech was not Latin, one could say that one must assume Sigenõð or Sigenõth are the personal names the Latin term represents. An exemplary reference appears in the Domesday Book of 1086. The Latin nomenclature clearly appears in the district of Reed in the Hundred of Odsey, Hertfordshire. The name may also appear elsewhere at later periods as Sinad or Sinodus. There are a number of later recorded instances as are presented from various sources in the table below. The Hertfordshire Domesday reference is justified as relating to an Anglo-Saxon individual on the basis that the 'Sinod' concerned had held the main tenancy at the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066. This was immediately after the death of the old English King, Edward the Confessor. One must infer that the Sinod individual had surrendered the holding in favour of the newer Norman Lord by 1086. This transfer was recorded as being under the reign of King William 1. One can easily recognise the similarity of both the Anglo-Saxon and Latin records to the modern variant spellings of 'Sennett'. However given the need to apply an academic or linguistic expertise to determine the phonetic or audial accuracy of a documented name, can one truly be sure it replicates the vocal or vocative speech of that time.

In circumstances where one wishes to ascribe a certain longevity to the usage of a personal name or surname, there would ideally be some continuity of both time and place in the usage of the name. Where such continuity is lacking, a problem arises as to how exactly or how precisely the recorded name of early times, should it have survived, was reflective firstly, of the ancient vernacular usage, and secondly, of its perceived conversion into a middle-English and later modern English documentary record. Certainty requires continuity.

Ultimately one is trying to delineate an unbroken linkage of names, one that can confidently connect the modern English language usage of a 'Sennett variant' surname with its multi-generational antecedent's ancient personal nomenclature. The issues one must address can be expressed a number of ways in the interrogative.

Was there continuous and consistent usage of individual family's Sennett-type surname in an English location.

Was that presence reflected in the available local or national documentary record?

Was the modern Sennett-type surname exclusive and discrete to a common group of Anglo-Saxon descent?

Was the surname's incidence of occurrence family related, or was it possibly co-incidental serendipity of fate?

The question may be whether and to what extent (over the required intervening period of almost 1,000 years), was the nomenclature faithfully, consistently and continuously replicated in the surname spelling of many generations of lifetimes. It is a long time to hold the human currency of surname identity. This question does not arise in Wexford. The surname has been there continuously and with frequency in that singular location in a range of common forms since the turn of the 12th Century.

A Sennett variant 'surname' may very well have been adopted in England after the 12th Century (when surnames came into use). The surname could have been adopted on multiple occasions, by unrelated families, and then thereafter wholly or partly expired. The incidence of the surname may have remained disparate and sporadic. This may be why the concept of a single Anglo-Saxon 'Sennett' genotype or haplogroup marker is problematic. The surname may never have achieved the weight and concentration of a family-name cluster. It could have remained widely spread throughout many English shires. Where its Anglo-Saxon adoption survived in England, it could have survived from multiple and separate sources. Perhaps the instances were quite unrelated in familial terms. Consequently each incident of occurrence could generate, in a collective sense, a multiplicity of genetic inheritance and markers. The surname could be polygenic. There is the possibility that an identifiable or singular Anglo-Saxon 'Sennett' haplogroup may be enigmatic or mildly chimerical. The premise of this paper or treatise is that the etymological surname dictionaries have been somewhat understandably subject to confusion and error. The Sennett surname in the historical British context would then be a representation in post Anglo-Saxon England of a 'convergence' with the variant spellings of the more singular Cambro-Flemish "E-M35" haplotype (classified similarly as haplogroup E-L117).

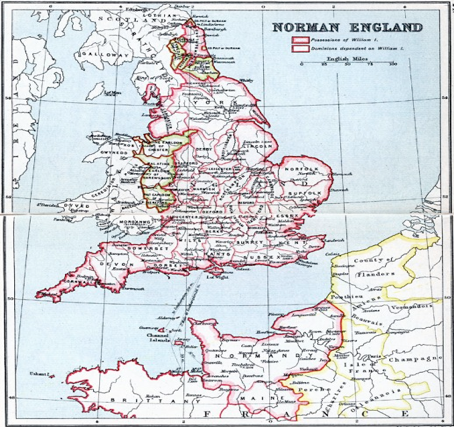

King Edward the Confessor's England at 1065

King William 1's England at 1087 (repeat of Ch.2.2/)

4.1b/ Anglo-Saxon Documented Incidence of Sennett and it's Published and unPublished sources

There is a sizeable record in English historical documents of 'Sennett' type family names or familiar and personal names. They are those names fairly comprehensively cited at each of the following English locations in the tabular listing below, at the specified dates. Most of the medieval and early modern instances of occurrence are repeated and partly replicated in the popular and respected Surname Dictionary selection. Those references following, relate only to the pre-Tudor period (pre-1485). At that time there was already an established sizeable cluster of Sennett bearers in South Wexford and its surrounds. The intervening 400 year period is book-ended from the point of William 1's valuation exercise in the Domesday Book of 1086.

The Domesday Book references to 'Sinod' (whatever the phonetics in Olde English or the Norman-French or Flemish vernacular may have been for that patronymic name at the time), do not make clear from their inclusion, whether the '3' recorded individual Sinods noted within, are Anglo-Saxon or Norman or Flemish in identity or whether perhaps they were of a mixed identity. The nature of these figures is unclear. One cannot be absolutely certain in one's description either way, unfortunately! It therefore may be best to treat the Domesday Book instances as a neutral prism through which to adjudge identity. One therefore must avoid judgment on whether these earliest documented 'Sinods' were more probably of either Anglo-Saxon or Norman-Fleming identity. The inclusion of the name may have been merely an incidental matter of no consequence to later surname descent or progeny. This immateriality of the record as regards the surname's dispersion would hold very true if the individual represented by an instance in the record remained without issue, or without issue that survived into adulthood, and equally so thereafter. The entries may very well have been merely coincidental with other Saxon records extant today, the Domesday entries being without surviving issue or direct continuity. In all, there are 5 citations of the proper name 'Sinod' in Domesday Book.

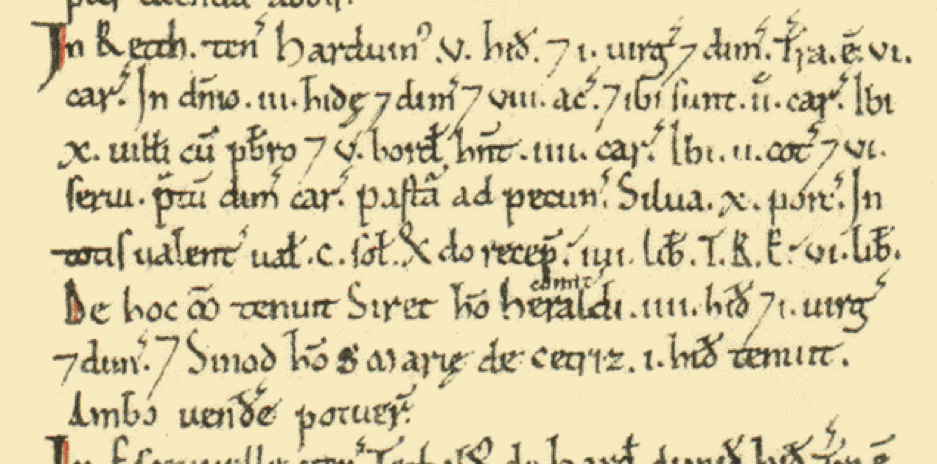

Domesday Book 1086 Hertfordshire, Reed in Hundred of Odsey, Sinod landholding in 1066 ('TRE' King Edward)

Extract above taken from the Domesday valuation survey in Hertfordshire, in Reed in the Hundred of Odsey. The section quoted comes under the heading of the 'Land of Eudo, son of Hubert'. Please see lines 5-to-7 above.

In 1066 (TRE) a "Sinod (or Sinad) the Abbot of St Mary of Chatteris's man, held land of 1 hide. He could sell".

Sinod (Sinad) was resident in Reed. Eudo was the King's Steward. A 'Hide' or 'Carucate' acreage is c. 120 acres.

Source: (http://opendomesday.org/place/TL3636/reed/).

Other Anglo-Saxon Documentation:

Aside from the surname's pre-Conquest presence among the Herfordshire' Domesday Book enumeration of 1066, there is other documentary evidence of its usage in the vernacular of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms. Those citations in original documents uncovered so far, go back as far as mid 9thCentury. A listing is presented below.

4.1B. Long Table/ Sennett Anglo-Saxon Documented Incidence in England, versus Ireland, below

| Chapter 4.1b/ Table 1: Sennett Anglo-Saxon & English Documented Incidence, (v. Sennett documented in Ireland). The available Irish record sources have been inset within the array of English document-sources in the Table. | |||||

|

Pre-Tudor records in England, versus the Documented Incidence in Ireland in Kilkenny and Wexford Counties. 'Sennett/variant' Incidence in Document Sources in England, cited in published works &provided by Sennett Group members (RMS,RJS,NHS,CC) The period concerns that prior to 1425 only, mainly 580 years from the enumeration of earliest Anglo-Saxons 844, to Domesday'1086, to 1425. |

|||||

| Year AD. 855 |

Sigenoth: In King Æthelwulf of Kent and successor King Æthelberht's reign, Sigenoth miles (soldier/layperson), 1 of 11 in Hse'hold 'Rise and Progress of the British Commonwealth' AngloSaxon Period, Pts I&II, Proofs &Illustrtns, (Fr.Palgrave, J.Murray,London 1832, p.271) and 'The English Church during the Anglo-Saxon Period AD.595-1066', A.W.Haddan &W.Stubbs, Clarendon Pr.1871 (Vol.'3, Ch.9, p.644/5) |

||||

| AD. 863 | Sigenoth: 1 of 11 individual 'ministri' attesting a Kentish Charter along with Ealdorman'Dryhtweald' (F.M.Stenton, Anglo-Saxon Eng.) | ||||

| AD. 844 - 1035 |

Sigenoth: 6 individuals of this Personal Name are listed in 'Onomasticon of Anglo-Saxonicum' @ years 844, 859, 860, & 1000-1035 'A List of Anglo-Saxon Proper Names from the time of Beda/Bede to King John (AD.672-1216)', WG.Searle, Cambridge U.Pr., 1897. |

||||

| AD.1016 - 1035 |

Sigenõth(aka Sinod/ð x2): During King Knut/Canute's reign, moneyer (mint holder) @London,'Sylloge of Coins of British Isles'(cn1/2) 'Moneyers of the Late Anglo-Saxon Coinage (1016-1042)', by Veronica J. Smart, 1981, PhD Thesis, Univ.of Nottingham, p.162/220. |

||||

| Pre-1066 | Regarding claims relating to Anglo-Saxon Chronicles (9x Documents), specific reference to a 'Sigenõð' or'Sigenõth' remains unfound. The Chronicles contain reference to Sigeat/AD.560, Sigebert/AD.754, Sigebright/905, Sigeferth/1015, Sigwarth/1043, not Sigenõð. | ||||

| 1066 | Domesday Book pre Battle of Hastings, Sinod (Anglo-Saxon Sigenõth or Sinoth) @Reed, Hundred of Odsey, Hertfordshire (&PNDB) | ||||

| 1086 | Post Battle of Hastings in 'Exon' mini Domesday Book, 2x Sinod (not Sionóid) at Sherborne & Beaminster Hundreds in Dorsetshire | ||||

| For published source Reference/Type, refer to Ch.3.2/ Summary Table in 'Surname Attribution in Historical works/+Dictionaries' | |||||

| CW Bardsley | Reaney &Wilson | Hanks, Coates &McClure | NHS (ftDNA member) | RMS (ftDNA member) | |

| DEWS., 1901 | DBS., 1958 | ODFNB+Irl., 2016 | (Nigel acknowledged) | (Rex acknowledged) | |

| 1095 | Synodus, Bury, Sufflk | Synodus, Bury, Suffolk | Synodus, Bury, Suffolk | ||

| 1130 | Sinodus, tenant of Geoffry deRos, Kent, fine to obtain inheritance (Rot.Pip. in Norman People &descendants, London 1874, & GPC 1989) | ||||

| c.1170's | Sinath (Sinad), Father/Antecedent? (regarding KilkennyCounty, Graiguenamanagh/Duiske Abbey, Charters No.2 below, of 1204) | ||||

| 1197 | Sinoth Cogno Phelaster, Kent, 8th Year of Richard'1 | ||||

| 1200 | one report Surrey/Stffs | RobrtusSinothi, Staffs | Robrtus Sinothi, Staffs. | Rbt.filius Sinothi, Staffs | Robertus Sinothi, Staffs. |

| 1204 |

Adam Sinath, Duiske Abbey Charters No.'2, Graignemanagh, Kilkenny Co. (p.147, St John Brooks -Knights' Fees, IMC, Dublin 1950) Son of Sinath, pre'1200, Kinsman of Maurice dePrendergast, Richard FitzGodebert &Rodebert (Robert) FitzGodebert/de la Roche. |

||||

| 1207 | Dionisia Sinod, Herts. | Dionisia Sinod, Herts. | filia Sinod, Herts. | filia Sinod, Herts. | |

| 1200-23 | Sinoth, Assize Rolls, +Curia Regis Civil Pleas, Lincs. | ||||

| 1247 |

Synach Knight's Fee (1/4 Qtr Fee in Feodary, via partition of Aymer de Valence/Lusignan Purparty, ex William Marshal Purparty), William Synach at Ballybrennan, Forth, Wexford County, (p.123, -Knights' Fees). Succeeded by John Synod, as at the year 1324. |

||||

| 13th Ct. | Sinoth, son Eterhamme, wtnss Cant.Cath.Priory, Kent | ||||

| 13th Ct. | Sinot+fil Sinoth, Land of St August'n Abbey,Cant. Kent | ||||

| 13th Ct. | Sinoth +Synoth quit claims, Cant.Cath. Archives, Kent | ||||

| 1273-75 | Rch/Slv Sunod, Hunts | ||||

| 1273-75 | Stphn Sinot/ut, Suffk | Stphn Sinot/ut, Sufflk | Stephn Sinot/ut, Sufflk | Sinot/Sinut, Suffolk | Stephn Sinot/ut, Sufflk |

| 1275 | Jak.Sunnota, Edwd'1 | ||||

| 1275 | John.Sunnot,Edwd'1 | ||||

| 1276 | Warin Sinat,Cambs. | Warin Sinat,Cambs. | Warin Sinat, Cambs. | Warin Sinat,Cambs. | |

| 1297 | Willm Seynde, Wexfrd | ||||

| 1324 | Calendar Inquisitions Wexford Post Mortem Aymer de Valence, 1324, Wexford County Feodaries of Sennett families (see above) | ||||

| 1338 | Matilda Synot, d. @ Lincs. | ||||

| 1379 | Johannes Sinhit,Yrks | Johannes Synet, Wilts. | Johannes Sinhit, Yorks | ||

| 1379 | Helias Senota, Yorks | ||||

| 1425 | Carew Mss, Lambeth, London, The 2nd de Valence Purparty partition among Co-Parceners, with Feodaries including Sennett lands | ||||

| 1549 | Martin Synnott, Ballyla | ||||

| 1549 | Will. Synnott, Mollestn | ||||

| 1552 | Will. Synote, Wexford | ||||

| 1558 | John Synnote, Wexford | ||||

| 1575 | Richard Synnot, Ballybr | ||||

| 1575 | Thomas Sinnott, Oxon | d. Nicolai Sennett/Senet (Will), Cottenham,Cambs.(CC) | |||

| 1579 | Richard Synote, Mallrg | ||||

| 1580 | Gilina Synnott, Wexfd | ||||

| 1601 | Walter.Synnott, Wexfd | ||||

| Ch.4.1b/ Table'2: Sennett record, Crown Excheq'r &Chancery's Patent Rolls, Close Rolls, Charters(13th-17thCents.) /RMS | |||||

| Search (access limited) of Roll Indices for Sennett on English Court Roll's websites, Roll Indices checked re Sin*** & Syn*** entries. | |||||

| Patent Rolls | Close Rolls | Charters | |||

| Years | Sovereign | Years | Sovereign | Year | Sovereign |

| # King John | 1214 Rudun de Sinot, Rotuli Litterarum Clausarum, (published William IV, 1833, p.201) |

# King john | John 1199-1216 | ||

| Henry III | Henry III | Henry III 1216-1272 | |||

| Edward | 1272-1279 p.71 Walter Sinolf, Imprisoned Cambridge, Cambs |

Edward | Edward 1272-1307 | ||

| Edward II | Edward II | Edward II 1307-1327 | |||

| 1338-1340, p.339 d. William Sinat, Kneb(s)worth, Herts. |

Edward III | Edward III | Edward III 1327-1377 | ||

| Richard II | Richard II | Richard II 1377-1399 | |||

| 1408-1413, p.450 Richard Synet, Chapl'n,Yatesbury Wilts |

Henry IV | Henry IV | Henry IV 1399-1413 | ||

| Henry V | Henry V | Henry V 1413-1422 | |||

| 1446-1452, p.369 John & William Synmet, (shipmen) | Henry VI | 1454-1461 p.341 Thomas Symnet, NewWyndesor/Windsor, Berks |

Henry VI | Henry VI 1422-1461 1470-1471 | |

| Edward IV | Edward IV | Edward IV 1461-1483 | |||

| Edward V | Edward V | Edward V 1483 | |||

| Richard III | Richard III | Richard III. 1483-1485 | |||

| Henry VII | Henry VII | Henry VII. 1485-1509 | |||

| Henry VIII | Henry VIII | Henry VIII. 1509-1547 | |||

| Edward VI | Edward VI | Edward VI. 1547-1553 | |||

| Mary Tudor | MaryTudor | Mary Tudor. 1553-1558 | |||

| Elizabeth I | Elizabeth I | Elizabeth I. 1558-1603 | |||

| Multiple i/net Searches, # Source King John <digitale bibliothek> | |||||

One might ponder whether, in its historical usage, the enunciation and interpretation of the surname in common vernacular English and the multiple documentary records was faithful to its original bearer's source and pronunciation. Would the name have remained true to its hearing and spelling, in repetition and replication, in all instances since it was first recorded in Latin or Old-English during Anglo-Saxon or later times?

Theoretically the more modern incidence of the surname in England and Great Britain could, as a hypothesis, have been mostly as a result of or follow historical inward migration or reverse migration to Great Britain from Wexford. This historical reverse migration would have been both pre-famine and post-famine in nature, although clearly it was mainly of the latter form. Regarding the former pre-famine instance of eastward migration to Britain, one can reference the remarks of G.H. Orpen in his work 'Ireland under the Normans' regarding the re-location of Wexford royalists to South Wales during Queen Elizabeth's Irish Wars of 1590s.

The hypothesis of Ireland as the springboard for overseas Sennett migration is indeed the case regarding the USA, and the old British Dominions and Colonies. The hypothetical case of the surname's derivation from Wexford is most probably in reality the actual case. The outward migration beyond Great Britain & Ireland would most likely have been from all or each of the provinces, Leinster, Munster, Connaught and Ulster. This is evidently so in the latter case of Ulster, where one can instance the re-location to colonial Australia of the much researched and historical Ballymoyer, Armagh County Synnots. The final Ballymoyer line of maternal descent, that of the Hart-Synnot family's male offspring is now expired (RVO Hart-Synnot having deceased at St John's Oxford in 1977, he being pre-deceased by his dear and much talented son, the Rev.ARP Hart-Synnot).

The American Atlantic states and the colonial Caribbean islands were also recipients of both indentured servants and non-indentured vagrants during the Cromwellian Commonwealth (1652-to-1660), and also thereafter. There was no doubt direct migration to the Americas and Colonies by those original South Leinster and Wexford born, former-resident 'transplantee' settlers of Cromwell's Connaught. This was an unremarked and quiet wave of 17th and 18th Century emigration. In the 1650s period it was partly under a contemporary enslavement. They went or were taken quietly and efficiently, and no doubt died without record or ceremony.

Should one accept the earlier stated premise of a Cambro-Norman-Flemish origin for the 'Sennett' surname, one should still not be tempted to disavow the evolution or existence of a true Anglo-Saxon derived "Sennett'. The line of this parallel but unrelated Sennett progeny is most certainly possible. Should the case become proven it would most likely be an instance of surname convergence from 2 separate sources, the Cambro-Norman of Wexford, and secondly, that of Anglo-Saxon England (East Anglia probably). There is some belief that there was a frequency and incidence of an Anglo-Saxon 'Sennett variant' surviving in the Home Counties, around London, and particularly so in East Anglia. This may be so. Such an occurrence should be of a distinct and identifiable Y haplogroup, distinct that is, from that which congregated around Wexford after 1170. This separate Anglo-Saxon Sennett haplogroup has as yet not been found (as at 2018). There is no genetic evidence to date of an identifiably English haplogroup for the Sennett variant surname. It could be that many or perhaps a few contemporary examples of such an Anglo-Saxon Sennett haplogroup remain in England but are still un-sampled. In time new evidence may well emerge that should clarify the shared surname's origins-conundrum.

One should instance however one of a number of indications of an Anglo-Saxon Sennett identity from the most ancient of records and perhaps the most ringing example of the associated Anglo-Saxon personal name 'Sigenoth' appearing in a late 1st Millenium context. It relates to the very subject of 'Names' and a group of 11 individuals in deep Saxon England (Kent) in the year 863. The citation is reported in 'Preparatory to Anglo-Saxon England: Being the Collected Papers of Frank Merry Stenton', editor Doris M Stenton, Clarendon Press (OUP), Oxford 1970, p.94 (rerinted 2000). The extract remarks on Saxon personal name conventions as follows,

"That history (of personal nomenclature in England) falls naturally into two periods, separated by the Danish wars of the of the 9th Century. It has already been observed that many stems which were still productive in the age of the migration became obsolete in the generations which immediately followed. With this reservation, it may be said that the character of English personal nomenclature underwent little change before the year 900. Most of the stems from which the names of the Lindisfarne "Liber Vitæ" are derived can be traced in midland and southern records until the time of Alfred.

(Alfred the Great,

Lindisfarne/Durham Liber Vitae, 825-1300 , not 9thCentury-to-1300 Winchester/NewMinster Liber Vitae)

A Kentish Charter of 863 for example, is attested by the Ealdorman Dryhtweald, by the ministri Mucel, Garulf, Eastmund, Wulfred, Wigstan, Ecgferth, Ealdred, Sigenoth (Sinod, Sennett), Elfstan, Wighelm and Wiatred, by the reeves Heahmund and Heremod, and by 32 priests and laymen, among whose names occur the compounds Noðheard, Diarweald and Beagmund, and the short forms Oba, Dudda, Lulla, Diara and Tida. What makes this variety of nomenclature remarkable is the narrowness of the social sphere from which the names which happen to be recorded in this earliest period are drawn. The West Saxon and Mercian evidence is supplied by documents which, with rare exceptions, give only the names of kings followers and important ecclesiastical persons. Little is known of the principles which governed nomenclature in families of humbler rank.

If, as is probable the clerks, monks and nuns of the Liber Vitæ and of southern ecclesiastical records were generally people of humble condition, it would follow that different social orders had not yet adopted different forms of personal names. In either case, it is certain that by the end of Alfred's reign few of the name elements used in the seventh and eighth centuries had yet fallen out of use".

A fuller listing of the bibliography of the Anglo-Saxon citation's used above in the two Ch.4.1b/ Tables (1 and 2) is provided in a special section of the 'Extra Bibliography' portion of Chapter 5.6/. The Extra Bibliography should list the more modern sources of these citations if not the original documentary record itself.

4.1c/ The Sennett & variant surnames in England: Research Appeal to readership of English Origin

|

Allocated Space: site's special notes to readers |

Research Appeal to English (Anglo-Saxon) Readership:

To all readers, but concerning males and male sample testing only!

If you have a 'Sennett-variant' surname and are of British heritage (of whatever race, nationality or language) and your family group also believes itself to be of an Anglo-Saxon genetic origin as inherited through the male line (for Y-chromosomal surname testing), please therefore do consider joining the

'Sennett & variant' single-surname Y-Chromosome Project at 'FamilyTreeDNA' www.familytreeDNA.com.

One can also email the administrator at the "Guild of One-Name Studies" at <sennett@one-name.org> , or view the profile page of the site at https://one-name.org/name_profile/sennett/, or a slightly less secure website address http://one-name.org/name_profile/sennett/.

Apart from the One-Name Study Group, if the surname is of potential interest, consult an ftDNA member, Rex, at site address www.sinnottNZ.com. Please do get in touch if desired and leave a comment on-site.

The outline of this paper is viewable on-line at http://synnott.org, or alternatively at www.synnott.org.

Any critical or constructive feedback regarding the text, do please message at Homepage or end of Ch.5.6/.

| Get in Touch/Send a Message: 2** |

4.1d/ Some brief words on name pronunciation over time (conceptually a difficult area):

One cannot actually be certain how a given name or surname was actually pronounced many centuries ago, especially in the historical setting of social and language evolution, different mother tongue or differing local-language dialects. A family's own pronunciation of its regular family name can be more conservative of preservation than that version which might appear in an historic written form, particularly for the illiterate. The written format as appears on the record might be noticeably subject to variable cultural or dominant language influences over time. It may also be subject to an arbitrary hand or the hand of state intervention.

The record of the surname (undoubtedly or reasonably with similar pronunciation) shows great variety of format in US Census returns of 19th Century. Generally in pronunciation, consonants can be applied very differently in different language cultures. Vowels have a tendency to slip and slide in their phonetic emphasis within the same culture over time. The influences of regional accents would be in addition and quite variable.

One might take as example the reported Anglo-Saxon format of Sennett, "Sigenõð/Sigenõth"

('Sinod' in Latin, and written as 'Sinoth' in later age's vernacular English of the Domesday Book translations).

In "Sigenõð" the 'g' was more probably a soft rather than a hard 'g', so giving it a 'Sin' or 'Sen' sound. Additionally the terminal 'ð' or 'eth', can be pronounced either like an 'eth' or even 'oth' sound, or alternatively with a stronger and more glottal 't' ending.

A further clarification of the Anglo-Saxon 'õ' sound remains a challenge. There are a variety of vowels in this format in Germanic/Nordic languages, with a range of phonetic pronunciations (as with 'Sennett' variants),

- O – the modern English letter 'O' variations, as with range of 'O' sounds from 'Oh Dear!' to 'otter' to 'other'.

- Ø – more of a short 'eh' sound of a soft 'E', as with 'Best of British luck' or 'bet the farm'.

- Ö – more of a strong 'Eee' sound of a long 'E', as with the 'E's, of 'ideal beetroot' or 'brush my teeth'.

- Ô – possibly more of a short or acute 'O' sound, as with 'pot a plant' or 'point the way'.

- Å – more of a long 'O' plus short & soft 'A'(mam/hat) rendered together, as in 1st syllable of 'boa constrictor'.

[constructive comment regarding pronunciation is welcome through Menu page's contact-email link, re 'text']

England in Year 1000, Reginald Piggott. http://edmaps.com/

England in Year 1000, Reginald Piggott. http://edmaps.com/

Alphabet,

England 1066, hubpages.com/education/domesday

England 1066, hubpages.com/education/domesday

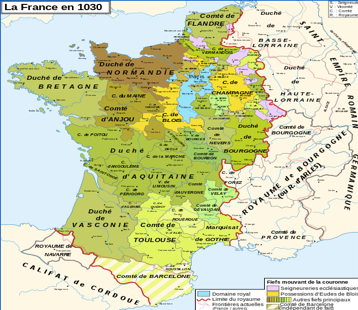

4.2/ France: Potential Origins in Normandy, Brittany, Anjou, Acquitaine (excluding Flanders)

France in 1030:

France in 1030:Duché and Comté, northern France

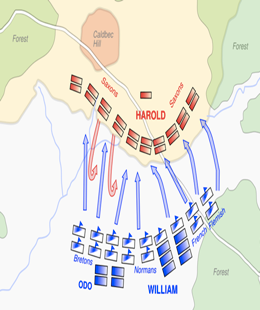

Norman Battle line @ Hastings 1066:

Norman Battle line @ Hastings 1066:Bretons, Normans, French, & Flemish(RHS)

John F. Kennedy in Wexford Town

John F. Kennedy in Wexford TownUSA'sAdmiral Barry Memorial '1963

4.2A/ The Gallo-Norman case for Sennett Origin (RJS re 'Val de la Sennette' acknowledged, & SSA acknowledged)

There is a limited case in favour of a truly Gallo-Norman source of Sennett descent prior to Wales. This is unlikely to be provable other than by ultimate success in establishing a DNA match with Wexford. As with the Flemish and Saxon cases for probable connection, the justification for a Gallic view of the surname's source need be explored and defined as best one can (an equal case could of course be made for Welsh origin). Ceertainly the Sennett surname Group might be of French origin. In such a case it would have migrated to England firstly, and then afterward through Wales to Ireland. All this probably within the long century between 1066 and 1200. This is logistically possible. The place of origin of one or more such individuals who had likely participated in the Norman invasion of England, could have been anywhere in a French territorial homeland.

The issue of the Sennett identity would then be curious. It is an undeniable fact that the Sennett name when present in Ireland, was most strongly associated with and also dependant upon the Cambro-Fleming sub-set of Knights and soldiery, those with a Flemish heritage. The possibility of such a long Franco-Flemish cross-cultural ethnic association is unlikely. If the Sennett name bearers were more truly French or Norman or Breton in character, and being originally from these territories in France, why would or why should, a mercenary individual or group of Francophone Gallic 'Sennetts' wish to associate closely with a mercenary sub-group of an identifiably Flemish character? The Flemings retained their identity over time through both the English and Irish conquest periods. Why would he (for it cannot be a she) or they choose to align closely with the fraternal descendants of Flemish mercenaries rather than Francophone Normans? Such a close association would need to have been established in France or Normandy or England or within Cambro-Norman society in South Pembrokeshire, in a changing and most dynamic context. This fraternity would need to have been established prior to the period between 1170 and 1200 at the latest (but probably prior to the period between 1110 and 1170, if not much earlier). Most of the aristocratic and leading members of the Fleming military which accompanied Duke William at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 had been despatched home to Flanders either soon afterward, or some few years later.

Listed below are some of the supporting facts or evidence that would complement and rationalise the belief in a more French or Gallo-Norman Sennett origin. Such an origin would be opposed to the more Cambro-Flemish wellspring of identity which this paper presents.

2A.1/ When Matilde of Flanders married Duke William of Normandy, she is reported to have brought 50 'knights' or men-at-arms with her as part of a dowry (reasonable for the time!). There actually was another set of allied Francophone and Breton individuals who were non-Norman in identity. They participated militarily in the Norman Invasion of England with Duke William. These participant members of the Francophone invasion would no doubt have remained loyal to the House of Normandy and the Kings of England for the following century (1066-to-1171). Such Francophone or Breton elements of the new ruling Norman class could equally have been part of a mercenary group (a Francophone gang probably), in similar fashion to any Fleming group.

2A.2/ The generic 'Sennett' Coat-of-Arms is displayed in the Concluding Chapter 5.3/. The Sennett, Sinnott and Synnott generic format of heraldic representation are all effectively the same. The Arms (or Blazons or Shields or Escutcheons) that have been awarded by the 'Ulster King of Arms', and later the Irish Chief Herald's Office (and possibly also the English 'College of Arms' in London) have tended to relate to the 'Synnott' or 'Synnot' forms of spelling exclusively. The generic Sennett Arms normally feature the heraldic device of 3 white or silver Swans set in a triangular array on red background (the 3 swans are said to be set close within the blazon (the shield) in the heraldic jargon. It comprises an upturned triangular arrangement of swans.

The individual family Coats of Arms that have been officially recorded and historically awarded mostly utilise the black swan as the main device (the swans being set 'close' in the triangular form, or 'pale' in the vertical form). The Synnott Arms officially granted are usually represented with black and silver colouring (sable and argent). The range of formats of the 6 to 8 relevant heraldic devices can be found firstly, in Burke's standard work "The General Armory of Great Britain (England, Scotland, Wales) and Ireland", published by Harrison of London in 1884 and subsequently reprinted. Secondly, there are two additional formats illustrated by a Crown sinecure office-holder of the time named Patrick Kennedy. He acted as Assistant Herald to the 'Norroy and Ulster King of Arms' in Dublin Castle in the early 19th Century. These latter two forms are illustrated in his standard compilation and reproduction of his work, known as "Kennedy's Book of Arms". This book was republished by GPC Publications, Baltimore. The adult Swan or adolescent Cygnet are potential elements of the Francophone case for the origins of the Sennett and variant surname. (see 2A.3)

Coats-of-Arms are now awarded to Irish citizens by the Office of the Chief Herald, exclusively. This is the successor Office to the old Dublin Castle heraldic role of 'Norroy and Ulster King of Arms'. It is currently a position held by the serving multi-role Director, Chief Librarian and Keeper of Special Collections at the National Library of Ireland in Kildare Street, Dublin. In England, Arms are awarded exclusively by the College of Arms in London (English and Welsh jurisdiction only). Arms are not nominally awarded to whole families, they may generally be inherited by direct descent and confirmation or affirmation to heirs in succession.

2A.3/ The French noun for swan is 'cygne'. The Sinnott/Synnott swan, and therefore the family whom it portrays as a heraldic device, could have originated from a place name such as that noted here, the village of 'Le Cygne'. It is located in the extreme northern region of France close to the border with Belgian Flanders, west of Ypres (Flanders), some way north west of Lille (France) and south of Dunkirk (beside the Belgian border and with its own placename 'Grand Synthe'). Le Cygne is within a Flemish heritage and historically Dutch speaking border zone, the Flanders border is but a stone's throw. Sennett has an obvious actual and phonetic similarity with 'Cygne/Cygnet' (translt., young or adolescent Swan). There is a phonetic similarity to its middle English translation of the name from Latinised form 'Sinod', to 'Sinoth/e' or 'Synath'. The village of "Le Cygne", lies in Arnēke Nord, in the Nord/Pas de Calais district. In recent years this wider area has been awarded the new regional name of 'Hauts-de-France' in the French Municipal structure. Le Cygne actually implies a 'Flemish' connection. Please cf. Elsdon Smyth's, 'New Dictionary of American Family Names'. Regarding his acknowledgement of adoption of 'signage' as a source of a surname, the same is also true for local landscape features in general, and of course rivers and river valleys.

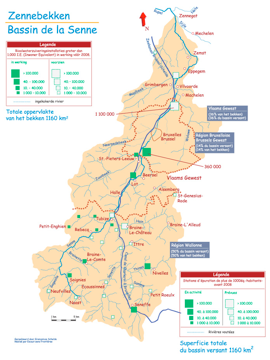

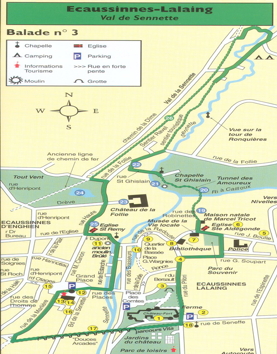

2A.4/ In the manner of synchronicity there is also a small and rather insignificant river 'Sennette' (by some accounts the Senette), somewhat further east and south-east of Lille, not far across the French-Belgian (Flanders) border. The Sennette's short life runs a northerly course parallel to the important Charleroi-Brussells canal to the town of Tubeke/Tubize (pop. c. 20,000). Tubize actually sits on the internal Flemish-Walloon border but is classified within the Wallonia zone of the wider farming area of the central Brabant region. Tubeke/Tubize (Fr.) is a small town with a minority Fleming community, majority Francophone. The Sennette is a tributary of the river Zenne /or Senne, which eventually progresses through Brussels as the left tributary of the river Dilje/Dyle. Brussels is a city which itself sits just north of the French-Walloon and Flemish language border of Belgium. The Dilje river in turn becomes the left tributary of the short & straight tidal river Rupel in northern Flanders. The Rupel then becomes the right tributary of the river Scheldt/Schelde as it flows towards the dual estuary entrance, a western and eastern channel, to the North Sea at the European port of Antwerpen/Anvers. Antwerp is located just south of the Dutch border and its southern Dutch Province of Zeeland at the mouth of the Scheldt. Along the Sennette and Senne River courses lie many dormitory towns. Some of these towns lie in 'Val' de la Sennette & Senne, Enghien & Commune d'Ecaussinnes (2A.4/ Graphic).

The Scheldt's true source is in northern France, in the old Department of Aisne. It passes through the Francophone Belgian Province of Hainaut/Hauts deFrance, before progressing on to meander through three of the five Flemish Provinces of Belgium, those of East Flanders (Ghent, its capital), Flemish/North-Brabant (Leuven) and finally the northernmost Province of Antwerp (Antwerpen). The city of Brussels in North Brabant is the capital of all Flanders and Belgium. Central Belgium has rich soils and enjoys the practice of agricultural cultivation in the Dutch style. The Province of Brabant, the largest central region of Belgium, has a component region in each linguistic zone and an intensive and attractive patchwork rotation of grain and crop production on its fertile rolling hills. It was not always so. Historically the Scheldt estuary and the river was an area that was much fought over in the early modern period from the 16th Century, and for centuries before and after. It has always been the location of much warlike dispute between the great European powers and ruling Crowns. Nearby to Enghien is the site of the Battle of Steenkerque where William of Orange fought and lost to the French Commander Marshal Montmorency, Duc de Luxembourg, during the 9 Years War in August of 1692.

Apart from the many local catastrophes of the last 20th Century, and the sharp and permanent cultural demarcation, the Scheldt/Schelde and the Senne rivers have often been part of a wider buffer zone between the great powers and an access point to northern France, the Netherlands (the United Provinces, then Dutch Republic) and the lower German city states. This region has not always shaped its own history. It was especially a zone of conflict during the European 'Nine Years War' of the 1690s and the 'War of Spanish Succession (1701-1714)'. There were also many long wars before. In the early modern period the region had historically proved a magnet to the covetous expansionary ambitions of the Bourbon Kings of France. The Scheldt estuary and Ramilles were other battlefield sites between 1691 and the early 1700s. The small Senne region's cultural duality in this sensitive location is as much a support to the idea of some Flemish Sennett identity as it is to the notion of a Gallo-Norman attribution. The only reason one need turgidly indulge the identity issue in this paper is because there have been many occasions in print, old and new, when the surname has been classed as possibly English or Norman or French. It is not because the idea is troubling, but mostly because it is so unlikely, that one must labour onward regarding the notion of an original identity.

Graphic 2A.4/ Gallo-Norman case, 'Val de la Sennette' near the Flemish-Walloon border region in Belgium.

Basin and Junction of Rivers Zenne/Senne & Sennette, near Tubeke/Tubize (Wallonia), & scenic town in Val de Sennette.

(c. 30 km south west of Brussels in Belgian Flanders): [RJS 'discovery' acknowledged]

The Basin de la Zenne/Senne, in Belgium

The Basin de la Zenne/Senne, in Belgium

Signpost 'Val de la Sennette'

Signpost 'Val de la Sennette'

'Val de Sennette' @ top (tributary of the Senne).

'Val de Sennette' @ top (tributary of the Senne).

2A.5/ There is also the possibility that the Norman, French or Flemish 'Sinad/Sinod/Synath' name migrated to England before its Conquest by William 1 (1066), if not long previously. This relocation could have occurred much earlier, during the 11th Century, but could hypothetically have been either side of Duke William's invasion of 1066, before or after. It probably did actually occur during a period when the low-lying coastal lands in France and Flanders suffered from severe flooding in the 1130's. Such a migration may also have been as part of an incentivised transfer of coastal dwelling linen and textile workers to southern England or South Wales, at any time. This did apparently occur at an early stage after the Norman Conquest. There is some record of mass coastal flooding in Flanders during both the 1110s and 1130s decades. There may have been comparable periods of dislocation with similar directional result of cross-channel migration at any time.

2A.6/ There are many attributed spellings of, and pronunciations for, the surname's variations in different cultures at different periods, eg., Sinad, Sinod (Latin), Sigenõð, Sigenõth (Old-English/Anglo-Saxon), Synad,

Synath (Anglo-Norman French, Anglo-Norman Irish), Sennett, Sinnett, Sinnott, Synnott etc (English, Hiberno-English, Yola) and Sionóid (Gaelic). There may have been both related and un-related or coincident occurrences of the surname in different parts of Europe. The diverse origins of the name may have converged in spelling. All of these surname variations may not be fully recorded in the surviving documentary artefacts.

2A.7/ There was already at the turn of the millennium (c. 1000) an occasional but sometime important exchange of trade (foods, horses, saddlery, textiles, timbers, wines, base and precious metals, weapons etc.) and traders or other persons and visitors, between Anglo-Saxon Britain or pre-invasion era England (before 1066) on the one hand, and France, Normandy, Brittany and Ireland and other European regions on the other. The attributed Doomsday Book references (to 'Sinod' in 1086) may signify either pre-invasion Sennett name-type occupation in England (1 instance), or post-invasion migration from Normandy, Flanders, Brittany or France (2 instances). There is always the possibility an original singleton Sinad or Synath, or perhaps a plural group of 'French' Sinad/Synath name bearer's, attached themselves and integrated into Gallo-Norman society at any time during that period. There were many representative elements of French society from other French regions among Duke William's Norman Invasion force, but a case for Francophone heritage overall does not add up to much. It seems less likely. Under full consideration it seems more to support the Flemish thesis.

4.2B/ The more romantic notions of a Sennett French-connection!

4.2B.a/ The 'de Valence' family in Ireland ('de Valence', a minor cadet branch of the 'de Lusignan' family).

There has historically been a presumption of linkage between the two family surnames, Sennett and Lusignan. This speculation is completely without foundation. It is stated and included here for historic completeness.

Isabel de Clare (Strongbow's daughter) married the eminent William Marshal/Mareschal (b.c. 1153). He was knighted in 1173 and on marriage (c. 1189), Isabel's inherited titles as sole survivor of her father Strongbow, including those of "Steward of Leinster" and Lord of Wexford, were added to the Marshal's own accumulating list. He became Lord of Longueville, Normandy (c.1191), succeeded as Hereditary Marshal, and in 1199 was created in his own right the Earl of Pembroke (of 2nd order) & Lord of Striguil (Chepstow).

Marshal was to prove most loyal to the new King of that year, King John. He was also made a Joint Guardian of England and Chief Marshal of the King's Court and Marshal of England early in the new reign, in 1200. King John was also known as 'John Lackland' (for his youthful lack of a Royal title) and also as the 'Bad' King John. He reigned from 1199 to 1216. In 1216, Marshal was appointed a King's Regent along with Sir Hubert de Burgh, during the early minority of the new monarch Henry III (1206-to-1272). Henry was not crowned till 1227. Sir William Marshal died in 1219. His titles passed on through his 5 succeeding sons, all of whom deceased without legitimate issue (dsp.) between the years 1231 and 1245. The sons died in some cases from jousting injuries - unlike their father. So, there was no surviving male issue. All 5 of the Marshal daughters married well and married into contemporary titled society.

The Marshal inheritance and the titled lands were then thereafter split between his 5 surviving daughters. One of these 5 daughter's own singleton daughter (mother and daughter both named Joan) married William de Valence (below), a supposed and accepted illegitimate half-brother to Henry III. The 'de Valence' family were a direct and sibling cadet line of the de Lusignan family.

The expired/or extinct Irish and Welsh titles of William Marshal's family and daughters, were awarded by King Henry III to a number of loyal supporters over a period between 1247 and 1251. By this means and by marriage the titled lands came to the hands of William de Valence. He of course gained favour through his claim to being the King's half-brother. William de Valence, Earl of Pembroke lived c. 1225-1296, his wife Joan being Lord of Pembroke. These titles later passed to his son Aymer de Valence (aka Aylmer c. 1280-1324), along with a newly acquired list of Irish and Scottish titles. William de Valence took up the cross in the period between 1270 and 1273. King Henry III was succeeded in 1272 by Edward 1, aka Edward 'Longshanks', who reigned from 1239 to 1307 (he was tall for the period standing c. 188/190 cms). Edward 1 consolidated his power in Wales by extensive castle building. He also took the Crusader's cross.

4.2B.b/The 'Synnot of Ballymoyer' citation of 'de Lusignan' family linkage and descent in Burke's BLG/LGI.

Until recent times there had been a belief in some quarters that the Sennett family name had been linked historically to the ancient French 'de Lusignan' family. The claimed linkage as a suggested fact was maintained for a brief period in the early and mid 19th Century editions of Sir Bernard Burke's 'A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain'. It was cited by Marcus Synnot Senior, of Ballymoyer' Armagh County, and first mentioned in the 1852 edition. It was also in a number of subsequent editions of Burke's "Landed Gentry" as published by Burke's Peerage in London. The later-published Victorian editions were known as 'The Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland', and 'The Landed Gentry of Great Britain', and separately 'The Landed Gentry of Ireland, (in 1899, 1904, 1912 and 1958). A still later version regarding Irish families only, was published as "Burke's Irish Family Records" in 1976 (last of 5 Irish editions).

The Lusignan claim was also cited in another work, Burke's 'Heraldic Illustrations' Vol 2., Plate 98, published c. 1844. The Lusignan connection was altogether dropped from the later Victorian and 20th Century editions of the Burke's volumes.

The founder and most prominent member of the Ballymoyer family was Sir Walter Synnot. Sir Walter was the 2nd son of Mark Synnot Senior of Drumcondra, Dublin (b.1696/98 d.1754, an elder son being Mark Junior b.1740 d.1789). Sir Walter was born in 1742, knighted in 1773, appointed High Sheriff in 1783, married twice and died in Rome in 1821. Marcus Synnot Senior, the eldest of his 3 son and 3 daughters, was born 1771, and d.1855. (The 2nd son, Captain Walter Synnot, was a noted soldier of the Napoleonic era, a settler-expedition leader to South Africa after the Napoleonic Wars, and a botanist, naturalist and ultimately pastoral farmer in Tasmania and Australia). Marcus Synnot Senior's eldest son Marcus Junior, married Anne Parker of Lincolnshire. There were no children of this marriage and when Marcus died in 1874 he was succeeded by his brother Mark Seton Synnot. Mark Seton died in 1890 leaving a son, Capt. Mark Seton Synnot and 6 daughters. Capt. Synnot died in 1901, unmarried and without children. This direct male line of the family having expired, Capt. Synnot's eldest sister Mary Susanna carried the female succession and established the Hart-Synnot (1902) line of Ballymoyer via marriage (1868) to the considerable military traditions of the English 'Hart' family.

The Lusignan linkage is nowadays taken as rather fanciful. The connection is none other than that as between a rather distinguished landlord and a sometime distinguished tenant. A closer linkage has never been proven in any way. For the sake of clarity and explanation, one can refer to a number of the interesting associations and amusing possibilities of the fate that cast the two separate families together. In full part the suggested linkage is incorrect with much of the presumption based on coincident background fact or very slight truths.

The most famed member of the de Lusignan family of Poiteau, was Guy de Lusignan, King of Jerusalem. From his rapid ascent of the Holy City's throne, one might say Guy was friend to none, and quite unpleasantly and wickedly bad. The major platform that provides a potential axis of connection (unprovable) with the de Lusignan family, was the fact that a member of the 'de Lusignan' family, Hugh X de Lusignan, had a son William de Valence, who along with his brother Aymer (both siblings of Guy), and William's own son another Aymer de Valence, would become Earls of Pembroke and Lords of Wexford in the 13th Century. The nature of this de Valence branch's inherited estate, a portion of Strongbow's and subsequently the Earl Marshal's Purparty Estate, was an inheritance through marriage into the Munchensy family's titles. William de Valence married a Munchensy daughter (aka. a member of the de Monte Canesio family). The Munchensy family can sometimes be confused with the Norman Conquest period family of Mont Marisco (aka. Montmorensy or Mont Mariscis). The Montmorency individual was originally an uncle by marriage to Strongbow.

The de Valence ascendancy in Ireland began between year 1247 and the early 1250's. The names de Lusignan and Sennett, and their connections through feudal tenures, was therefore purely a function of the de Valence land inheritance and ownership and its subsidiary feodaries (tenancies). One should not really progress that fact into a thesis of closer relationship. As was stated the de Valence family's direct connection with Ireland and Wexford began in 1247 with their assumption of the title of Earls of Pembroke. This is more than 40 years (or more than one generation) after the documentary record of the Adam Sinad/Sinath/Synath in Kilkenny County in year 1204 regarding the Cistercian Order's Duiske Abbey (or as called nowadays, Graiguenamanagh Abbey). This was a quit claim in favour of King John's tenant-in-chief (landlord), the Earl William Marshal.

4.2B.c/. Points of coincidence or overlap between the Lusignan family and elements of Norman history.

Listed below are the more interesting facts of the 'de Lusignan' or 'de Valence' family parallels, coincidences and resonances with Norman history, and the Norman Invasions of England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland.

c.1/ The de Lusignan (or de Valence) family name, was of an aristocratic or royal line on its own account, rather like Duke William of Normandy. The surname originated in Lusignan, a town commune where there remain trace foundations of the ancient family castle, destroyed during the 17th Century wars of religion.

c.2/ The Anglo-Norman Kings of England, the Houses of Normandy, Plantagenet and Lancaster took titles from, and came to have interests in those provinces of France near Lusignan, ie., Anjou, Angouléme, and Aquitaine.

c.3/ The historic prominence of Lusignan Castle and Commune of the Vienne Department in the region of Nouvelle Acquitaine. It is located in Charentes Maritime, between the towns of Nantes, Poitiers & Angouléme.

c.4/ A bearer of some form of the 'de Lusignan' name may have participated in the Norman Conquest of 1066.

c.5/ There were some linkages between the ruling Houses of Normandy, Flanders and Aquitaine through Duke William's marriage to Princess Matilde of Flanders. William's marriage to Matilde took place in 1050.

c.6/ Matilde of Flander's mother Adèle was daughter of Robert II, King of France. The King's parents were Hugh Capet and Adelaide of Aquitaine. The Provence of Acquitaine contains Poitiers, Angouléme, Lusignan.

c.7/ There was a misguided notion in a number of Victorian publications that the surname 'Sennett' was of the French family deriving its descent from the Marquis de Lusignan. There is clearly no justification for such claim.

c.8/ The de Lusignan family originated at Poitou, near Poitiers in mid-west France. They controlled the family Chateau, the Castle of Lusignan at a time when it was the largest and greatest fortification in France. The family branch that remained in France had many domestic titles, Lords of Lusignan and Counts of La Marché, Counts of Eu (in Normandy) and Counts of Angoulemê. These titles represented prominence in the area and later the family's importance in the Middle East and Mediterranean during the Crusader period. The de Lusignans became allied with the English throne after the death of Richard the Lionheart in 1199. He had spent many years on Crusade and in hostage captivity. In a failed attempt to consolidate his French possessions in Acquitaine, Richard's successor King John (1199-to-1216) attacked the region and town of Lusignan. During this siege of Lusignan, Hugh le Brun (aka Hugh de Lusignan IX, Count de la Marche, d.1219) negotiated a simple and dignified surrender of the Castle on behalf of the Lusignan family. There was an ongoing Anglo-French war (1202-to-1214) in France through most of this period of King John's reign. He lost his French territories in 1204.

c.9/ Some of the more notable families in Ireland after the Norman Conquest (1171), and during the Over-Lordship of King Henry II in Ireland (1172-to-1189), were related to the French Lusignan family, ie. the de Clares (Strongbow's Pembrokeshire family), the de Lacys (in Ulster), the de Warrennes, the Munchensys (aka Monte Canesio, through marriage to William de Valence), and de Montmorency (aka Mont Marisco, P.H. Hore cites a Geoffrey de Mariscis, History of Wexford, Vol.5, p. 28). The 'de Valence' family of this period had become a cadet branch of one of the de Lusignan family's lesser ranking siblings.

[There was a sizable historic house-contents auction at a 'Montmorency' estate home, Kilkenny Co. in 2014.]

c.10/ The de Valence family titles relating to Ireland were as 'Earls of Pembroke' (3rd Order) and also 'Lords of Wexford' (3rd Order). There was no established 'de Lusignan' presence in England in the Anglo-Saxon or early Norman periods, prior to William de Valence's (b. 1225) Welsh and Irish titles held c.1247-to-1296. His son Aymer or Aylmer de Valence (1275-to-1324) then succeeded to the title. Aymer de Valence inherited the Irish & Wexford estates through his father in 1296. He had therefore a feodary connection to all his feudal tenants.

The first recorded instance of Sennett (Sinad/Sinath/Synath) in Ireland, was in Kilkenny County in year 1204.

This citation of Adam Sinad and his father a 'Sinath' or 'Synath', precedes any direct connection of the Valence or Lusignan families with Ireland. Likewise, the tenancies and feudal feodaries taken up on the assumption of the Marshal family's purparty by Aymer de Valence (assumed between 1247 and 1252), follows behind the establishment of the surname in Ireland. There could not be a true familial relationship between the two.

Section references

("History of the Town and County of Wexford", P.H. Hore, Harrison, 6 Volumes, London 1900-to-1911)

("Knights Fees in Wexford", Eric St John Brooks, Irish Manuscript Commission, Dublin 1950)