2/. Flemings in Wales, Ireland and Wexford under the Cambro-Norman order Download

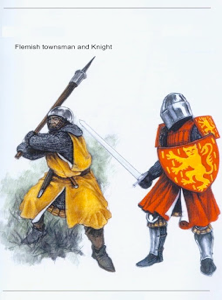

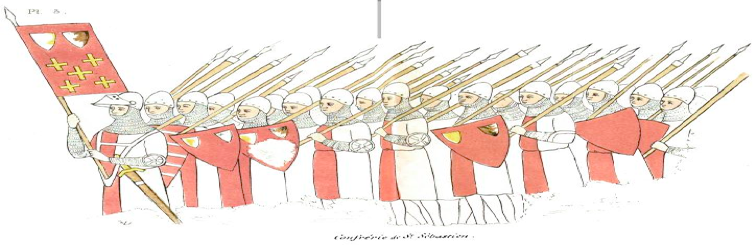

The 2 rival Gaelic Kings, Dermot & Rory, 5 Irish Provinces, and Flemish Town Infantry (Bruges) 1250-to-1350

Count Balwin V of Flanders (1012-1067) & Countess Adèle Capet (Antique Print)

Richard FitzGilbert deClare (1130-1176) NGI Gallery (Maclise) Strongbow's Marriage

William Marshal (1147-1219)

(Wikipedia.org)

William Marshal (1147-1219)

(Wikipedia.org)

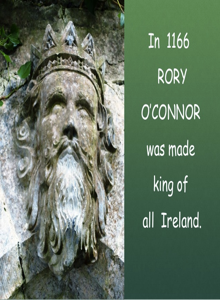

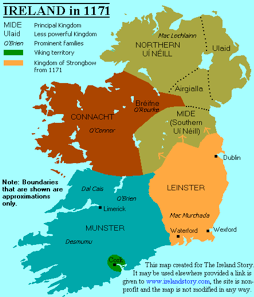

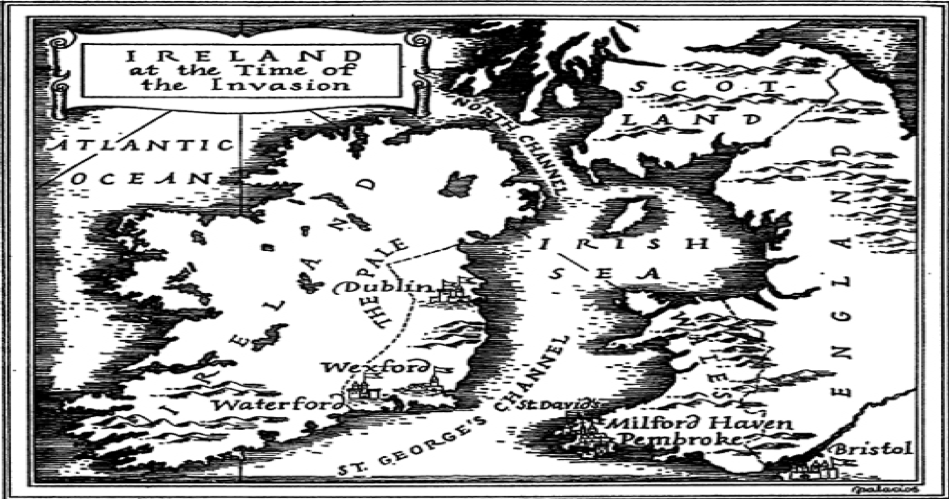

King Dermot, High King Rory 1166-1171, Ireland's Provinces @1171 www.theirishstory.com, Fleming Infantry

2.1/ Wexford before Cambro-Norman-Flemish Invasion 1167-to-1171, and the Vatican

The Ireland of that time, similarly to today, was a country comprised really of the 4 major provinces, the ancient provincial Kingdoms of Leinster, Munster, Connaught and Ulster (although one might add another lesser northern Leinster Province, that of Meath, now Meath & Westmeath Counties, or in the Irish-Gaelic language "An Mhí" or 'Mide'). Each provincial Kingdom was under the Kingship of a particular clan, the McMurroughs, O'Briens, O'Connors and O'Neills respectively, in regard to each of the 4 major Provinces at that time. One might also add to the preceding list the territory of the O'Rourkes of Brefni in north west Leinster due to its prominence in the history of that period. Each of the 4 or 5 Provinces would additionally be comprised in turn of lands and territories ruled by numerous regional sub-chiefs, the chiefs of clan. There were a large number of these lesser lands or territories or fiefdoms, large and small, within each Province. These fiefdoms or bailiwicks of clan rule and territory might comprise an area of similar or lesser size to that of the later Norman land divisions, the county, barony and cantred (county being also called 'shire' in England).

Most of the settled and fertile lands of the country remained in the hands of these Gaelic Chiefs and clans and their followers and kinsmen. Across the country at a local and regional level, much of Ireland remained in an inconstant and irregular state of civil war during the 11th and 12th Centuries. There were many causes of conflict, many alliances and rivalries and territorial feuds, many lesser and larger chiefdoms and fiefdoms, and much blood shed and lives lost on one or other local chiefs behalf. The middle of the 12th Century before the Norman Invasion was not an unusual period in this regard. This was the case also in Wales in the 11th Century.

Apart from the main territories, the port towns were sometimes at peace with their surrounding hinterlands, but also sometimes at war. The Norsemen or Norse-Irish of the time (Vikings, who were more Norwegian and Scottish Isles or even Irish born, than perhaps Danish born as was the case in England), had established many port towns and waterways around the coast, those of Dublin, Wexford, Waterford, Carlingford, Strangford, Cork, Limerick and Galway. The Norse towns tended to be inhabited or co-inhabited on civil and trading terms with the local Irish Gaels or indigenous Irish, these 'Town' Gaels being to some extent the Norsemen's local allies. The towns of Dublin, Wexford and Waterford were the most important maritime centres. These vital trading ports to the Irish Sea accessed all of the coastal regions of north-west Europe. There had been trade links and links of alliance between some of the Norse towns, and the formerly factional Danish and newly emergent Anglo-Saxon 'English' Kingdom between the reigns of Alfred the Great and Edward the Confessor.

In Ireland, the Kingdom of Leinster included a particular regional Gaelic Lordship within its southern domain, that of the "Uí Ceinnsealaigh", ruled by a clan of the same surname, the Clan Ceinnsealaigh (Kinsella). Its territory constituted most of the modern Wexford County. There were a few smaller demarcations of territory in coastal South Wexford, those of the Gaelic lands of "Uí Bairche" (later, under the Norman land division, the Barony of Bargy), and "Fotharta" (later, the land division or Barony of Forth). It was in these two Baronies (in the Norman parlance, 'Cantreds'), especially in Forth, that the surname would later become more numerous in frequency in Wexford during the 14th-to-16th Centuries. They would be granted by King Dermot to FitzStephen.

Under the ancient Gaelic "Brehon Law", all the provincial Irish Kings ruled under a nominal High-Kingship. At a certain point this High-Kingship was held by King Rory Ó'Connor (Irish Gaelic: Ruairi Ó'Conchuir/Conchubair, 1116-to-1198). He was also the reigning King of Connaught, the more western of Ireland's 4 main Provinces. Rory was notionally High King of Ireland between 1166 and 1186, but in reality not-so beyond year 1171, the year of King Henry II's visit to Ireland. King Rory's compatriot and fellow Provincial King was the King of Leinster 'Dermot McMurrough' (aka, Ó'Murchú, McMurchada, or Murphy). King Dermot at this time in the mid-1160s had long held good communication and cordial relations with the English Court, and Dermot himself had family relatives living in the Port of Bristol in Gloucestershire in the English West Country. A bitter dispute erupted and remained in play between King Dermot, Chief of the MacMurrough clan of South Leinster and his allies on one side, and his rival Rory Ó'Connor of Connaught, the nominal High King of Ireland, and Rory's ally, the clan-Chief Tiernan Ó'Rourke of Brefni in north east Leinster, on the other. King Dermot's family, the MacMurrough's, would later hyphenate their surname, the family and Leinster clan title later becoming that of 'McMurrough-Kavanagh'.

King Dermot in exile

King Dermot was deposed as ruler of Leinster in 1166 by King Rory. He lost control of his lands in eastern Ireland to his military rivals, both the High King, King Rory of Connaught, and Rory's Leinster ally, Chief Tiernan O'Rourke. King Dermot wanted Anglo-Norman military and mercenary help. He met with King Henry II in Aquitaine in western France later in 1166. The meeting was to seek the English King's support to regain full title, status and position in Leinster. King Henry II's future proxy ruler in Ireland, Strongbow (aka the Earl of Pembroke, Richard FitzGilbert de Clare of South Wales), was enlisted to lead the Irish campaign by Dermot.

Strongbow would later marry the ex-King's daughter, Dermot's daughter Aoife (aka Eva), in October'1170. The marriage took place soon after his arrival in Waterford. However, the state of relations and the level of trust between the two Norman leaders, Henry II and Strongbow, were frail. The 'de Clare' family had earlier opposed Henry II's mother's claim to the English throne, that unsuccessful claim of the Empress Matilda, the daughter of Henry I (aka Empress Maude) against the preceding English King, Stephen (reigned 1135-to-1154).

Henry II, Henry Plantagenet (aka the botanical Planta Genesta in its Latin form) had inherited his Crown in 1154. He did so unusually not directly from his grandfather Henry I who died in 1135, but rather through his mother Empress Matilda or 'Princess Maud', the daughter of King Henry I. Matilda was titled Empress after her 1st French marriage. Matilda's 2 nd marriage had also been made in the French Court, to Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou. Empress Matilda's succession, although previously announced by the dead King Henry I, had suffered her claim to the throne being usurped and replaced in the succession after Henry's death. The new claimant was the former King's nephew, Stephen. The new King, King Stephen or Stephen of Blois, Count of Boulogne and Duke of Normandy, was the son of William the Conqueror's only daughter, Adéla. King Stephen and his spouse, yet another Matilda, Matilda of Boulogne, reigned for almost 20 years until Henry II's succession. Henry's ascent of the English Crown signified an end to the old Norman ruling family, the House of Normandy, and the commencement of the reign of a new Royal family, the Plantagenets. Henry II married the divorced Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1152, two years before he became King. Her family succession extended his Royal domain to the western seaboard of France. Eleanor was the former wife consort of King Louis VII of France.

King Dermot of Leinster met with Henry II in France. Henry II granted King Dermot a general licence to enlist what militarised Knights he could find as mercenaries for his cause in Leinster. Thereafter King Dermot recruited to his cause Richard de Clare (in Wales, aka 'Strongbow') and his local Norman Knights and supporters and various ancient and newer allies among the Welsh Marches on the England-Wales border and in the Norman colony of South Pembrokeshire (this latter region was really a 'Pale'). King Dermot hoped to fully reclaim his throne in Leinster with the help of Strongbow and his new Cambro-Norman mercenaries.

Strongbow's family were distant relatives of the old House of Normandy. The English Court after Henry I's death had been divided into those who supported King Stephen (reigned 1135-to-1154) in his claim for the throne, in opposition to Henry II's mother, Princess or also then Empress Matilda, daughter of Henry I. The early period of King Stephen's reign was one of civil war, Matilda having gained a brief ascendency between 1140 and 1141. Strongbow was not entirely trusted by either side in that conflict. He owed his full allegiance to the new ruling Plantagenet line, that of King Henry II (reigned 1154-to-1189). It is worth noting that as early as 1155, a newly crowned King Henry II had talked of a possible invasion of Ireland at the Council of Winchester.

Henry's reign in a later 20 year timeframe saw him claim Ireland within his Royal Angevin realm. His Kingdoms would eventually comprise for a short period in the late 12th Century (until Bad King John's reign began in 1199), much of a contiguous Plantagenet or "Angevin" Empire in western Europe. It would notionally comprise Northern & Western France, England & the Principality of Wales (Wales was then still a Kingdom), the separate Kingdoms of Ireland & Scotland and the Isles, plus the Channel Islands (see Ch. 2.2/ end, Graphic Maps of England). The little local squabble between Irish Kings in Leinster in the mid 1160's, was accompanied by 2 other contemporary and important events. These events were perhaps not quite as carefully noted as they should have been by the three Irish Provincial Kings concerned, the 3 principals of the bitter rivalry in Leinster.

The role of the Vatican in 12th Century Irish affairs

Firstly, the conflict and conquest of Leinster had been preceded by a Papal Licence (a Laudabiliter, or Papal Bull or Bill), granted directly to the newly reigning King of England in 1155 by the then Pope. Pope Adrian IV (a Nicholas Breakspear), the only English Pope, had given this Licence to Henry II after his succession to the English throne in 1154. The Irish Christian Church traditionally observed a certain independence from Rome, an distinction protected by the provincial Irish Kings. Such independence of observance and the divergence and aversion of the Celtic Church from Rome's direction and conventional Christian practice, was an affront to both Rome and Pope. The Laudabiliter granted King Henry, as the English monarch, and Canterbury Cathedral as the English Church, authority to bring the Irish 'Celtic Church' under conventional Anglo-Christian control. It could be seen as a grant of Licence to Invade Ireland to the King (then not yet the King of England & Wales). The advance licence was offered with the Holy approval of the Vatican and the Pope. It is now assumed in most academic circles that the documentary copy of the Laudibiliter Papal Bull of 1155 in the NLI Library (as part of a manuscript text of Giraldus Cambrensis's Expugnatio Hibernica work) must have been replaced and altered from any original version under direction of Cambrensis. There is no such original in Vatican or British Archives. Any amendment to the real record was so as to favour, justify and empower King Henry's Irish remit.

Secondly, there was also at the time, within Rome's Catholic establishment in England and its many separate Holy Orders of Faith, a desire by the English Order of Augustinians to gain a firmer primacy among the existing Roman Orders in Ireland. The former King of Leinster, King Dermot, had encouraged in the 1150s, the founding of an Augustinian Abbey in Ferns. Ferns was the notional capital of his Leinster Kingdom. The Order's model and founding Christian, the Benedictine monk and Roman educated 'St Augustine' of Canterbury, the 1st Archbishop of Canterbury, had been given the task of taking Christianity to a largely pagan Anglo-Saxon southern England by the Roman Church, in AD.596. At that time, Ireland, Northern England, Scotland and the Islands were already Christian. The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were mostly pagan at the time.

Separately, there was even a further resonance in history with the old Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms in Britain. Two pioneer warriors, the Jute-Saxon leaders and fraternal duo 'Hengist & Horsa', had originally been invited into England by a native Britannic King, Vortigern. They were invited to Britain to help Vortigern violently suppress his rival opposition among other British chiefs and tribes between AD.430 and 450. The Jutes decided to stay.

King Henry II visited Ireland in mid-1171. His visit was initiated with a sense of urgency, and signalled the consolidation and completion of the full conquest of South Leinster, the desired realm of direct Norman influence. The completion of the conquest of South Leinster (the neighbouring region of Ireland to Britain), had been immediately preceded by the murder of the Bishop of Canterbury, Thomas a'Becket, in December 1170. The murder of Thomas a'Becket by Henry II was conducted through the proxy of 4 of his loyal Knights. He was murdered in his own Cathedral at Canterbury. The Norman conquest of Ireland would be part of Henry's penance or contrition for this murder, seen as an outrage at the time. Henry had appointed Becket.

Strongbow's Irish conquest had been in progress, but not fully completed, since August 1170 and had only recently been executed. This initial stage of the campaign was secure enough for Strongbow to claim one of his trophies, his bride, King Dermot of Leinster's daughter. Strongbow married the King's daughter, Aoife McMurrough, in Waterford in late October 1170, (only 2 months before Becket's murder). King Henry may have been of the view that if Strongbow felt secure enough to marry quickly, the King should establish his own Over-Lordship of Leinster equally quickly. So, if the King had to go to Ireland, he might easily as well end Becket's term of service as Archbishop of Canterbury, efficiently and conveniently, beforehand. Then he might seek forgiveness of the wicked deed through his good works in Ireland. King Henry II was contrite, apologetic, and penitential after Becket's very public murder. The two events, the marriage of Strongbow, and the murder of Becket, were really quite contemporaneous. In Roman or Christian terms, one act could be excused and forgiven by the other. The murder could be granted forgiveness by a completed conquest of Ireland.

So, fortunately, Strongbow's expedition having met with success, King Henry might from that point forward, and notionally under his own Over-Lordship, be able to gift to Rome a subjugated Irish Church. It could be offered as an action of contrition. It would convey an Irish obedience to Rome henceforward and a new order could then be imposed on the Celtic Church in Ireland by their new Overlord, the King of England. The Irish conquest would reinforce King Henry II's state of penance after the murder. The re-orientation and control of the Irish Church would be for King Henry a further justification for forgiveness in Rome. It would also secure a new compliance and acceptance among Henry's own and recently, most troublesome English Church. The English Church would be run by a new and more loyal Archbishop in Canterbury.

2.2/ Flemings in Norman England & Norman Sth.Wales (& Scottish Borders), & Exon Domesday Book.

Count Balwin V of Flanders (1012-1067) & Countess Adèle Capet (Antique Print)

Richard FitzGilbert deClare (1130-1176) NGI Gallery (Maclise) Strongbow's Marriage

William Marshal (1147-1219)

(Wikipedia.org)

There seems to be some evidence of a Norman (or Fleming) Sennett's temporary or extended stay in England, contemporary with the Norman Conquest period. Within one generation of the Norman Invasion, apart from England itself, there would be Flemish communities and Flemish vanguard populations at the Scottish border lands and on the South Wales frontier, the Marches. There appears however to be no documentary evidence of particular Sennetts in the far northern English/Scottish borderlands or Norman South Wales (or even in Ireland), in the intermediate post English Conquest period, that period between say 1070 and 1200. However, in coastal England there is evidence of specific Sennetts within this range of time. It is most clearly recorded there. One doesn't know or can't be sure however if this evidence is that which relates to Flemish, or Norman, or French or 'Anglo-Saxon' individuals. The references don't provide other evidence of an identity (not at this stage, and not until the pendulum of this history moves to Ireland). The 2 main points of this English Sennett reference could of course also be claimed as evidence of an Anglo-Saxon name origin, but only if rather special or unusual circumstances had prevailed in their particular cases, at the date of the Domesday record in 1086.

So the name references come from the Domesday Book of 1086, or more correctly, the mini Exon Domesday Book of the same year. The main Domesday Book is an Exchequer Valuation of England's land and real estate and all of its infrastructural and agricultural assets, south of the River Tees. It comprises 7 leather-bound regional Volumes, these being Volumes of Inquests. They collectively record the asset ownership for each County and 'Hundred' within the English sovereign realm, as held under the ruling monarch at 2 different dates. The dates were firstly, as at 1066 (TRE- Tempus Rex Edwardii, the time of King Edward the Confessor) and again in 1086, under King William I, William the Conqueror and Duke of Normandy. The Domesday survey's coverage of Dorset, the English County on the south coast, contains 2x Sennett (Sinod/Sinoth) references. It was conducted as part of another separate but contemporary regional Domesday Book, one exclusively related to the south western region of England. This latter book was known as the Exon Domesday (2 smaller Volumes). A reproduction of both of the Dorset County texts follows nearby below.

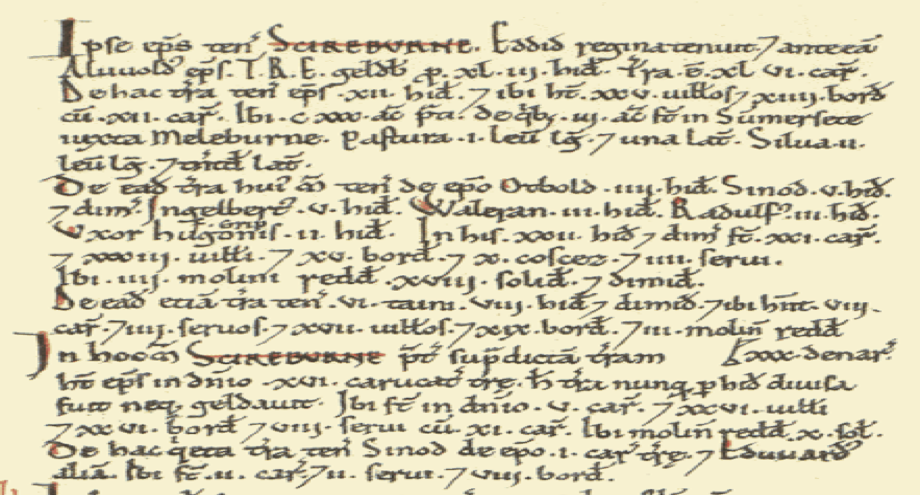

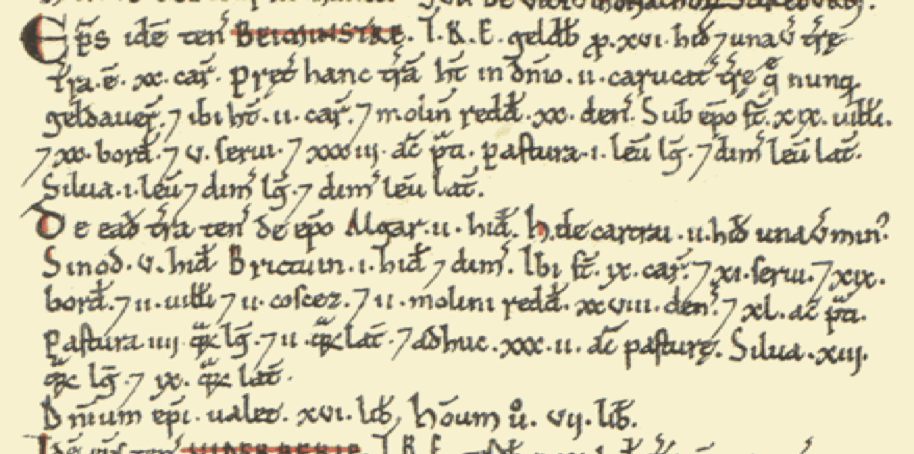

Sennett (Sinod) in the Exon Domesday Book of 1086, 2x Dorset County entries "Sinod/Sinoth".

There exists in common Surname Dictionary reference a particular or better known Sennett citation of a 'Synodus' at Bury (Suffolk, East Anglia) at year 1095. The citation is placed in a wider English context in a Table in Ch.4.1B/ later. It is not known whether it bears any relation to 2 "Sinod" Domesday Book entries of 1086, those in the settlement Hundreds (Districts) of Sherborne and Beaminster in Dorset. Such an inference would require some record of further information which seems not to exist. In one of the 2 Domesday cases there is a plurality of reference to a 'Sinod' named individual, the 1086 listing for Sherborne cites multiple entries (3) under the Sinod attribution for property holdings. There is a singular citation at Beaminster. All are recorded in Latin. Both these two named 'Sinod' individuals however (supposedly two), in either place, hold sub-tenancy property (leases) in two neighbouring Hundreds. They are both under the new King William's local Lord Tenant in Chief, the Lord Bishop of Salisbury's St Mary's Church. The status of these 2 Sinod individuals seems as that of either Freemen or Vassals in each instance, not lowly 'villeins', unfree tenants, cottagers or peasants.

As stated the Sinods both held tenure from the Lord Bishop or head-leaseholder, the Bishop of Salisbury's Cathedral Church of St Mary. This feudal land-holding Lord was also in situ at Beaminster in 1066, but the reported Chief Tenant in the Sherborne Hundred at the earlier date of 1066, was 'Queen Edith'. This was a literal case of "elite transfer". Queen Edith (Edith of Wessex c. 1025-to-1075, December) was the former Queen of England, her husband was the aged King Edward Confessor who quietly deceased in New Year 1066.

Edward and Edith had married in January 1045. King Edward was King Harold's predecessor, that same Edward frequently mentioned in the text used in Domesday Book, and referred to as 'TRE'. Therefore this particular Sherborne property was ultimately held under a most noble Anglo-Saxon title at this earlier 1066 date. Overall, while only 1% of the English population was Norman in 1086, the new Norman ruling class held all but about 2% of the Norman Lordships. There were c. 800 Norman Lordships in England in total at the time of Domesday. A new Norman estate owning elite held former Anglo-Saxon lands, it comprised 5,000 families.

This presence might therefore suggest the 2 Sinods concerned (presumably 2), were loyal subjects of the newly ruling King and possibly among that new ruling class of Anglo-Normans (or Anglo-Flemings). However, from the Domesday manuscript one cannot be absolutely certain that the new assignees of the lands concerned were among or allied to the new Norman conquerors. One might say just that they were more likely to be so. Overall the Great Book recorded the transfer of property from Anglo-Saxon (1066) to Norman (1086) hands. It is of course possible that these 2 named individuals could have been solo or twin remnants of those older times, two retained Anglo-Saxon tenancies. This would be less likely. Good land is not overlooked.

There is an additional and different 'Sinod' (with a conventional translation as 'Sinoth') referenced in the main Domesday Book's text, in the district of Reed, in the Hundred of Odsey, Hertfordshire. This citation should most probably be considered as of an Anglo-Saxon person, the landholding being recorded as held under the local Lord at the time of Edward the Confessor, this being before the Norman Invasion of England in 1066. The new English King before the invasion, King Harold Godwinson, had only come to the English throne in January 1066, after the death of his predecessor King Edward during the New Year period. This Anglo-Saxon Domesday 'Sennett' identity, or the possibility of such an identity, is considered in the later and more focussed Anglo-Saxon section (see Chapter 4.1/).

A proper Flemish, French or contemporary Anglo-Saxon pronunciation of this Latin name 'Sinod' must be speculative. One cannot know exactly what the surname's real exclamatory sound was to the ear (the Latin 'Vocative'). The vocal form of its expression and its appellation of address in the vernacular of the time, may not one could believe, be replicated nowadays with an absolute certainty. Nor can one really be sure of what the 'Sinod' individual's Latin nomenclature and spelling in a text represented audially, truly and faithfully, other than that it was specific. An Anglo-Saxon heritage in its bearer might suggest it represented the name Sigenõð or Sigenõth. If the bearer were of Flemish, Norman or French heritage, the exact vernacular nomenclature it might have represented among the bearer's own peers at that time is uncertain. One might think and hope it represented the name of Sinod, Sinoth or Sinothe for the Anglo-Saxon faithful (Sinad, Sinath, Synad & Synath for Hibernians).

The 2 Domesday Book reproductions from the Dorset County Exon Domesday Book's text, follow below…

i/. Firstly, for translation see further below.

[The insert sub-script '7' in extracts shown below is abbreviated to act as textual syntax, a form of semi-colon; ]

The text above concerns the Sherborne Dorset entry in the Domesday Book of 1086. There are 2 entries for 'Sinod', 5 hides being held in Sherborne on first line of second paragraph. A hide was sufficient land to support one household (120 acres). In the penultimate line of the whole passage there is another parcel of land which appears to be 1 carucate. A carucate was similar to a hide, but more exactly being a plot of land offering one season's ploughing to a full plough team of 8 oxen. Both lots were held under the Bishop (St)Osmund of the Cathedral Church of St Mary's of Salisbury. Source: (http://opendomesday.org/name/492000/sinoth/).

ii/. Secondly.

In Beaminster Dorset, it appears Sinod (or Sinad) held 5 hides at this time, see line 7 above. The land here was also part of the estate of the Bishop (St) Osmund of the Cathedral Church of St Mary's of Salisbury.

Source: (http://opendomesday.org/name/492000/sinoth/), GDB 77 (Dorset 3:10).[Hide/Carucate= c.120 acres]

Below is a translation of both the relevant segments of the above Exon Domesday entries. (RJS acknowledged)

i/ Sherborne translation:

The Bishop holds Sherborne himself. Queen Edith (the previous King, Edward's spouse Edith, daughter of Earl Godwin, Queen Edith d.1075) held it, and before her Bishop Alfwold (Bishop of Sherborne, served 1045 -to- 1058) . Before 1066 (TRE. Time of Rex Edward the Confessor) it paid tax for 43 hides (each c. 120 acres). Land for 46 ploughs (each plough comprises team of 8 oxen). The Bishop holds 12 hides of this land …

Also of this manors land Odbold holds 4 hides from the Bishop, Sinod/Sinoth 51/2 hides, Englebert 5 hides, Waleran 3 hides, Ralph 3 hides. The wife of of Hugh's son Grip 2 hides. On these 221/2 hides are 21 ploughs. 33 villagers (high status peasant), 15 smallholders (middle status peasant), 10 cottagers (cottage peasant)and 4 slaves (landless peasant). 4 mills which pay 181/2 s. (s. a shilling, or 12 pennies) Six thanes (a holder of land granted by the King or military nobleman, ranked socially between ordinary freeman and hereditary noble) hold 81/ 2 hides also of this land. They have 8 ploughs and 4 slaves and 17 villagers and 19 smallholders. 3 mills pay 30 d. (30 pennies)

In this manor (of) Sherborne, besides the said land, the Bishop has in lordship 16 carucates (each c. 120 acres) of land. This land was never divided into hides and did not pay tax. In lordship (land farmed directly be under-tenant himself/herself) 5 ploughs. A mill (annual 'shilling' rental paid to Lord's manor) which pays 10 s. Of this exempt land Sinod/Sinoth holds 1 carucate of land from the Bishop, and Edward also. 2 ploughs; 2 slaves; 8 smallholders.

In this same Sherborne the monks of the Bishop hold 91/ 2 carucates of land which was not divided into hides and never paid tax. In lordship ( land farmed by under-tenant directly) 31 /2 ploughs; 4 slaves. 10 villagers and 10 smallholders with 5 ploughs. 3 mills which pay 22 s; meadow (common land for making hay), 20 acres; woodland 1 league long (imperial 3 land-miles, 4.8 kilometres) and 4 furlongs wide (imperial 4 x220 yards, 4 x200 metres) …

Further, in addition to this, Sinod/Sinoth holds 1 hide from the Bishop in the same village; he has 1 plough there, 2 slaves and 2 smallholders. Value 12 s. Alward held this hide from King Edward, but previously , however, it had been (part) of the Bishopric. [synnott.org website author's comment: Sinod took occupation 1066-86]

ii/ Beaminster translation:

Before 1066 (TRE, King Edwards Time) it paid tax for 16 hides and 1 virgate of land (circa 30 acres, 1/4 of a hide, or 2 old Danelaw 'oxgangs' ). Land for 20 ploughs …

[Middle lines] Also of this land, Algar holds 2 hides from the Bishop. H (Humphrey) of Carteret 2 hides less 1 virgate, Sinod /Sinoth 5 hides, Brictwin (or Brecwin) 11 /2 hides. 9 ploughs there; 11 slaves. 19 smallholders, 2 villagers and 2 cottagers. 2 mills which pay 28 d; meadow, 40 acres; pasture, 4 furlongs long (imperial 4 x660 feet, 4 x200 metres) and 2 furlongs wide; a further 32 acres of pasture; woodland 13 furlongs long and 9 furlongs wide. Value of the Bishops lordship £16 (16 pounds sterling); of the men's £7.

The Historical Fleming Trajectory: Flanders, Hastings, England, Pembrokeshire and Wexford

Other than in the Domesday Book, any Sinod, Sinodus or Sigenoth-named documented reference in the newly conquered England of the 11th Century or soon thereafter, ie. during the period between the Norman Invasion of England (1066) and the Invasion of Ireland (1169-to-1171), could hypothetically be of either Flemish or Anglo-Saxon or French origin. Unless the citation is accompanied by valid supporting information as regards true identity, one would be guessing. One might take the view that one can not easily be sure of one's grounds for attribution of an identity in this period. Any particular given name (if not quite a surname) might have been referenced in the Anglo-Saxon vernacular, the Norman-French form or as a more official Latin script. It is unlikely to have been recorded in Flemish or Dutch. The application of the nomenclatural conventions could have depended on the enumerator or recorder's own arbitrary hand. The name might refer to a party of either Flemish or Saxon origins. It may be best to be agnostic as regards the source-place of a very few citations of record in this 100 year period, without favour. One may allow that probability may justify a more partial view.

The members of this surname origin group described earlier as Cambro-Norman-Flemish are therefore probably the descendants of the same group of mercenaries who arrived from Flanders firstly to newly Norman England. They migrated secondly, from King William's England, to the relocation settlement in South Pembrokeshire (Welsh: South Dyfed). This group and its descendants represent that Flemish character of the mercenary group that later preceded and accompanied Strongbow's Cambro-Norman Invasion of Ireland. This Irish conquest replicated Duke Williams Invasion of England a century earlier only in some ways. The Irish Invasion, during its actual period of execution over a number of years, was really comprised of 4 or 5 successive dis-embarkations on the Wexford and Waterford coast. It was not a single event, more an ongoing process of attrition in battle and territorial acquisition. All of these took place between 1167 and 1170. Strongbow arrived only in August 1170 with his own mercenary knight/cavalry (c. 300-to-400 in number), archers and men-at-arms (c.3000) in August'1170. Some hard fighting had already taken place but much battle remained before the Invasion force and its Irish allies could claim a sustainable success. The leader Strongbow, married the former Leinster King's, Dermot McMurrough's daughter Aoife (aka Aife or Eva), in October 1170.

Soon thereafter, in September 1171, the busy new 'Angevin' Overlord and new 'King of Ireland', King Henry II of England, arrived and stayed to over-Winter in Ireland. The purpose of the visit was to consolidate his sovereignty over the new Kingdom among his Norman warlords. The new King was still then in a state of contrition following the acknowledged murder of the Archbishop of Canterbury in December 1170. He would come to a practical compromise with the High King of Ireland, King Rory O'Connor, regarding the OverLordship and sovereignty of the island. Henry II would act as the ruling monarch of Dublin and South Leinster and its port towns. King Rory would offer his 'fealty' or notional subjugation regarding the rest of the island of Ireland, but still retain actual control. This compromise settlement did not last many years, the Norman Knights remaining in Ireland being soon tempted to conquer new territories in all directions and corners of the island.

Chapter 2.2/ References (further reading)

William the Conqueror's (William I) Exon Domesday Book 1086, 2x Dorset County entries, cf. "Sinod/Sinoth".

The Normans in South Wales 1070-1171, Lynn H Nelson, Univ of Texas Press, Austin & London 1966, LC.65-21296.

"The Flemings in Pembrokeshire", Henry Owen, Archaeology Cambrensis 1895, Series II, Vol. XII, p.96-p.106.

Ireland c. 1170 William 1's England c. 1087, Henry II's Angevin Empire c. 1189

2.3/ Pre-Invasion Flemings in Pembrokeshire (Haverfordwest, Rhos, Roose & Roch Castle), and

[Ch.2.3/ Appendix: St Andrews University's ISHR-Institute of Scottish Historical Research, text later]As yet there is only substantial genetic evidence to date of one common origin within the wider Sennett surname group, that one derived from a Wexford Sennett cluster. This static cluster most likely originated with a solo or low frequency of bearer/s among the congregating Flemings in South Pembrokeshire (south Dyfed) in the early 12th Century (soon after King Henry 1st succeeded to the English crown). There may or may not have been an actual or preceding cluster in South Pembrokeshire, one can't know. If there were such, it is probable they were and remained close to a FitzGodebert family orbit during this pre-surname formation (or adoption) period. It may likely be that one can never know from surviving records among available Welsh,English,Flemish sources. Wexford seems the only known regional clustering of the surname found during these ancient times.

This surname of sorts appeared in very early times in a documented form, as recorded in both Latin and Anglo Saxon script, in both Leinster and England. A proper documentary surname record of the period is unknown to date in Wales, or it is possibly awaiting discovery. However, only in Wexford was the document record followed by a static and continued clustering in the surname's incidence and presence. The proper attribution of a surname source does require a specific location. It also requires the following factors: an initial or core numerical weight, some lengthy continuity of location and finally, a process and period of dispersion. The initial numbers involved of course, could fundamentally be one, a singular and sole progenitor of the name.

A single progenitor is the simplest form of attribution a genealogical trail can determine. An early "Sinath/Sinad" individual was recorded in a Kilkenny County lease reversion of 1204, he being the supposed father of an Adam Sinath/Sinad, and grandfather of a David FitzAdam Sinad/Sinath. David himself appears a decade or two later in an undated land grant in Fernegenal, the territory north of Wexford Town and Harbour (possibly Farringmall in recent centuries). These individuals may or may not be the progenitors of the Sennett surname, but they are the earliest identifiable persons in Ireland of that name. The early Cambro-Norman Wexford population, and the increasing Sennett frequency there, seems to be the only clustered source of the dispersed but commonly shared genetic marker that has been found world-wide to date, (this may change).

In Wexford the Sennett surname had a close 'kinsmen' association with other known Cambro-Fleming families, those known to have been living in South Wales before 1170. Thereafter they lived in post-Invasion Wexford or South Leinster or Munster. Among the Flemish who settled in Wales, one such prominent historical figure and family was 'Godebert Flandrensis de Ros' and the descendant 'FitzGodebert' or 'de la Roche' family. This "Godebert of Flanders" 1096-to-1131, is named in a Crown Exchequer Pipe Roll of Henry I, No.21/3, dated 1130. This family as we know had their homebase fortress at Ros or Rhos Castle (Ross/Roose/Roch), in the Barony of Roch, near Haverfordwest, South Pembrokeshire (Welsh: Dyfed). The town of Pembroke on the River Cleddau, and the Port of Milford, neither being too far from FitzGodebert's Rhos or Roche Castle, would in time become important ports to the Irish Sea among this long established Flemish colony. The South Pembrokeshire colony itself was a cultural and fortified "Pale". It was imposed on the local Welsh inhabitants of south-west Wales and fortified along the indigenous population's hinterland by a line of newly-built castles.

The slow Norman Conquest of Wales

The Norman conquest of Wales was a very gradual affair. The advance into Wales took place intermittently through many decades over 200 years of Norman advance (Ireland would take 400 years). The conflict against the Welsh Princes was first initiated in 1067 soon after King William I's arrival in England. The Norman armoured fist did not hesitate in action against its neighbours. The immediate onslaught across the river Severn continued intermittently until 1081. It was quickly followed by another campaign under William II, known as William Rufus. This conflict continued until the mid 1090s. The advance had started in the Welsh Marches of south east Wales and continued disjointedly to coastal North Wales and even to far off Anglesea, (just as in ancient times 1,000 years before, then under the Roman Governor of Britain Gaius Paulinus, AD 60).

The House of Normandy's ongoing attempts at conquest would also include campaigns under Henry I (1114) and Henry II (1157 with Roger de Clare, and again in 1163). The conquest of all Wales would prove to be a prolonged multi-reign affair and a rather attritional to-and-fro. The Conquest was not completed until the reign of the Plantagenet King Edward I (reigned 1272-to-1307). This final and successful multi-year struggle against the Welsh resistance lasted until 1283. His adversary was the Prince of Wales, Llwelyn ap Gruffydd (aka. Gruffud or Llywelyn Ein Llyw Olaf, 1223-to-1282).

The plantation of coastal Pembrokeshire by anglicised Flemings had been promoted in the early 1100s by King Henry I. Henry (1068-to-1135) was also known as Henry Beauclerc. He was William the Conqueror's 4th son. Henry I succeeded King William II (Rufus), the Conqueror's third son. William Rufus died while hunting near London in year 1100. The tragic incident remained somewhat mysterious. William the Conqueror's 1st son, Robert (aka Robert Curthose, or Robert 'Shortleg') always remained in Normandy and succeeded his father to the Dukedom of Normandy. King William's 2 nd son Richard had earlier died in a hunting accident in 1070, also at the New Forest, and the same location of death as his younger brother William Rufus, 30 years later. The plantation process in Wales took place soon after Henry's succession to the English Crown. The actual plantation to the Pembroke region probably took place after 1105, and probably from about 1108. Many British historical sources say between 1105 -to- 1108. The King would reign for 35 years after 1100. He had earlier championed the advance of the Norman conquest of South Wales, across the River Severn and through the south eastern Welsh Marches. Gilbert de Clare, 2nd Earl of Clare, Lord of Tunbridge (Kent) and Cardigan (Wales), and a son of Richard FitzGilbert de Clare (a cousin to King William I), would lead an expedition of Norman forces into South Wales in 1107. This Richard deClare was the grandfather of another Richard deClare, aka 'Strongbow', the leader of the successful Cambro-Norman expedition to invade and conquer Ireland.

In the 12th Century, the Pembrokeshire colony possessed a sharp linguistic line, a clear linguistic demarcation now more recently known as the "Landsker Line", running east-west through the south of the shire. The colony was known colloquially as 'Little England beyond Wales'. This cultural divide was reinforced by the building of secure stone fortresses throughout the southern Pembrokeshire region during the 12th and 13th Centuries. Henry I initiated this Fleming plantation early in his reign to distance his new Court from his long deceased mother Matilde's old Flemish allies. The coerced migration of the Flemings to Pembrokeshire would also hopefully help pacify a rebellious and still Britannic South Wales, outside of the Welsh Marches at least. The new Marcher territories and counties lay west and north of the Rivers Avon, Severn &Wye, beyond Bristol. As at the time of distribution of this paper, no record of 'Sennetts' have been found in South Pembrokeshire or South Wales relating to the period 1100 -to- 1200 (as far as one knows). Today, there are a number of Welsh Sennetts with two preferred spellings, Sinnett and Sinnott, modestly present in the Principality. It is assumed these are returned emigrés rather than 12th Century. Certain back-migration occurred in late 16th Cent. (&17th).

King Henry I, aka Henry Beauclerc, had a mother named Matilde of Flanders, a 1st spouse Matilda of Scotland (d.1118), a daughter Matilda - known as Empress Matilda and also known as Princess Maud, and also finally a Matilda being the spouse of his successor King Stephen, he reigned 1135 -to- 1154. All of these close women family-members were called 'Matilda'. The Normans were very particular in their use of first names, or Christian names. The pattern would spread to their family names. They only changed their surname nomenclature, the naming conventions, in the 12th Century when they dropped the ever altering father's patronymic, in favour of retaining a particular patronymic surname. Henry I and his young 2 nd spouse, Adeliza of Louvain (m.1122), remained without a male successor, if not quite childless. Henry's intended heir, his only son 'William Adelin' had drowned in a shipping accident off Normandy in 1120. The tragedy, a fire aboard ship while setting forth into the English Channel, is known as the 'White Ship' incident.

The distinctive character of this 'Little England' territory in South Wales was soon thereafter further reinforced by the probable inward migration of textile weavers and others from Flanders, in either or both of 2 decades in the 12th Century, the 1110s and/or the 1130s. It is believed these migrants and new outlanders had suffered a period of particularly heavy continued flooding and dislocation in their coastal continental homeland at these times. They may have received some sympathy from the English Court and southern English port populations. This was no doubt prodded by historic links of felicity and affinity with Henry's deceased mother, Matilde. Henry died in 1135. The special character and language of the Flemish colony amid its indigenous Welsh hosts in South Wales, was something that would in time be replicated by the nature of the Cambro-Flemish and Norman settlement in the South Wexford baronies. These settler baronies bordered on other territories that largely remained wholly or intermittently under the control of the indigenous Irish Gaelic clan-chiefs. As was the case in Wales, in Wexford and Ireland there remained a long conflict of attrition between settler and clans. The Norman advance in Ireland was, firstly, noticeably curtailed or extinguished, and then neutralised and absorbed into the indigenous Gaelic society by the end of the 13th Century, and the early 1300s.

As was the case in South Pembrokeshire before 1170, the newer settler people in south Wexford and south Leinster mixed and mingled with their host clans (O'Rourke, Kavanagh, Kinsella, and Murphy clans), most especially in the towns. Sometimes this was peaceably achieved, but often it was a result of long or attritional conflict in newly seized territories, particularly in north and mid Wexford, also Kilkenny and Carlow Counties.

This mixing is certainly true in South Wexford, evidenced by the cross-current admixture of place-names that remain, a plural collection of Norse (Weisfjord, Oilgate, Selskar, Bunargate), Cambric (--ton/town names), Norman-Flemish (Ross/Roche), Gaelic (--bally/baile) and Anglo-French family/or townland names. There is also evidence of adoption of Gaelic 1stnames by Anglo-Norman families in mid-Wexford in 16th Century. (ref. V, & W) The same sense of special character would likewise descend on the counties of Ulster following the period of Ulster Plantation after the initiation of the 1st Foyle river plantation scheme, in 1607-to-1610. That plantation began in Derry/Londonderry (aka Doire) in the years after 1607, and then included the surrounding counties of western Ulster, the area west of the River Bann. East of the River Bann, the two coastal Counties of Antrim & Down were earmarked for Scots and Borders settlers. The Kintyre peninsula is visible from north Antrim coast.

Henry I's plan in South Pembrokeshire had employed a similar strategy and scheme to this later one adopted by James VI of Scotland in Ulster after he inherited the English crown. James had ascended the English throne in 1603 as James I of England, his succession being earlier approved and agreed by his unmarried predecessor, Queen Elizabeth I. King James initiated the Ulster Plantation by promoting the project with the City of London Craft Guilds, and also by facilitating and incentivising the transfer of any troublesome northern and Scottish Border region's reiver-families to the Ulster counties. The migration project would promise either land or prospects or power for its participants. The urgency and similarity of the two projects, South Pembroke and then Ulster, is noteworthy. The later Irish trans-plantation was effected when James I was only 4 years into the new reign. The start date of that project was only some 6 years after the defeat of the Ulster Chiefs, O'Neil, O'Donnell and their Ulster Earls by the then reigning English monarch Queen Elizabeth, (Battle of Kinsale, 1601, Cork). King Henry I's transplantation project to Pembrokeshire, the first of many such Royal plantations, was implemented between the 5th and 10th years of his reign, after 1105.

The Prominent Flemings

The FitzGodebert family mentioned earlier above would mostly be known in Ireland as the 'Roche' or 'Roach' or 'de la Roche' and even the 'de Rupe' (in Latin) family. There were additionally from South Pembrokeshire the Busher, Cheevers, Prendergast, Sennett, Siggins, Stafford, Stephen and Whitty families among others, all from this small Cambro-Flemish element of a Cambro-Norman colony near Pembroke.

These collectively participated in Strongbow's Cambro-Norman-Flemish invasion force between the initial reconnaissance (1167) and the actual conquest (1169-to-1170). Henry II and his Anglo-Norman entourage arrived to claim Ireland's OverLordship in mid 1171. The actual conquest initially progressed through the south-east of Ireland in a forward and backward fashion. The initial reconnaissance mission lead by King Dermot of Leinster and his Cambro-Flemish ally FitzGodebert in 1167 was quickly and briefly successful but eventually failed and fell under threat. It had progressed from the Wexford coast to Ferns the regional capital, and then Carlow, where it was defeated by the local Irish forces. It then retreated home to South Wales. The Invasion properly did not start till mid 1169 with the arrival of the vanguard body of Marcher Knights and their leaders (listed above). Then, for most the year following, there was a considerable and bloody to'ing and fro'ing of territory and towns between the indigenous Irish-Gaelic and Hiberno-Norse allies on the one hand, and the Cambro-Norman-Flemish military (and their own Irish-Gaelic allies, those allied to King Dermot), on the other. The invader forces were often but not always lesser in number. The conquest was as much a matter of attrition or process of capture, rather than a one-off conquering event such as the Battle of Hastings.

The Norman taking of Waterford, Wexford and Dublin, was achieved after modest rather than great battles. King Henry II's visit of 1171 was to consolidate control of the Leinster territories and towns and demand a Royal sovereignty and Over-Lordship over all of Ireland. This remained for centuries after, but was a largely a notional sovereignty. King Henry visited Ireland in 1171 with an Anglo-Norman force of about 400 Knights and 4,000 men-at-arms. It travelled between Waterford, Dublin and finally departed from Wexford. He soon compromised with the High King, Rory O'Connor (O'Conchobair) on the notional sovereignty of Leinster and Ireland, the King retaining direct rule over only the southern half of Leinster and its main port towns. The three towns, Dublin, Wexford and Waterford had been until then Norse (or Viking) strongholds and sea-ports of vital trade and regional influence. While the Invasion phase was a brief two years, there was also subsequent to the Invasion itself, some further or continued migration to Wexford and Dublin from Pembrokeshire and South Wales. Both of the Knights of Flemish descent, Rodebert/Robert FitzGodebert (de la Roche) and Maurice de Prendergast, had been strong allies of, and granted Wexford lands by, their fellow Cambro-Norman 'Strongbow', King Dermot's ally. Prendergast was promised his Wexford lands by Strongbow as an incentive to continue his participation in the Irish project.

Strongbow was the true leader of the Irish Invasion after its first foray in 1167, but he did not arrive himself until 1170. Members of both of these Flemish families were part of the important early Flemish-Cambro-Norman reconnaissance and engagement in Ireland between 1167 and 1170. The earliest land grant after the Invasion, that concerning two particular 'cantreds' or baronies near Wexford Town (Forth and Bargy), was made by King Dermot of Leinster to the Knight Robert FitzStephen.

Strongbow (Richard FitzGilbert deClare) family's later inter-marriage with Fleming leaders

Strongbow's proper name was Richard FitzGilbert de Clare, c.1130-to-1176, he was the 2nd Earl of Pembroke (of 1st Order or Earldom) and also Lord of Striguil (now Chepstow, in Monmouthshire, in the South Wales Marches). Strongbow inherited the titles from his father Gilbert de Clare, the 1st Earl of Pembroke and likewise Lord of Striguil. This Gilbert de Clare was the grandson of another similarly named Richard FitzGilbert de Clare, 1st Earl of Clare, the Norman cousin of William I the Conqueror. The first Richard was the Commander of King William I's Norman army on the Invasion of England and at Hastings in 1066. It is believed the younger Richard de Clare was born at Tonbridge (near Tunbridge Wells) in Kent where the 'de Clare' family held the title of Lords of Tunbridge. Richard's (Strongbow's) mother was Isabel de Beaumont. He would give his only surviving daughter the same first name. His other child, Gilbert (3rd Earl) died a minor c.1185. The author St John Brooks also mentions Strongbow's 2nd daughter Alina. She supposedly married William (FitzMaurice) FitzGerald, 1 st Baron of Naas, Kildare County (d. 1199), son of one of the Invasion's leaders Maurice FitzGerald. This additional Cambro-Norman link is acknowledged by most historical accounts.Members of the Fleming' de Prendergast and de la Roche families would later marry into the FitzGeralds of this Naas family line in the 13th Century.

At this point it may prove useful to promote other's knowledge of this most

interesting but little known region of the UK, and its lesser known

history, particularly ancient history. It would be best to hand over to an

acknowledged academic source on the topic of old Pembrokeshire. In the

nature of life, apart from the Welsh Universities which might also fill a

real gap with their own clear and factual history, it was a Scottish source

which came first to hand in a timely fashion and from an unexpected source

(and so saved much searching). It was a case of a needle being found, but

not being found near the haystack. The source is St. Andrews University in

Scotland, particularly its 'Institute of Scottish Historical Research'. The

Institute is no doubt an off-shoot of the University's History Department.

The author obtained the text below from one web posting, sent as the

content of one long-past update item and belatedly considered. It is

reproduced almost in full immediately below. The particular posting was

consulted after the narrative above had been many times drafted and

scribbled. The posting was put up on the University site on 2nd

May 2015, by a Ms Amy Eberlin. A modest list of the bibliographical sources

cited and a long list of previous website postings should be included at

the end of the Extra Bibliography (ref Chapter 5.6/ below). The author of

this paper was made aware of the ISHR's work and website

and its relevant content by an industrious and dedicated acquaintance,

unexpectedly.

Sincere thanks, CC-O acknowledged.

Ch.2.3/Appendix:Pre-Invasion Flemings in South Pembrokeshire (Haverfordwest,Rhos,Roose &Roch)

St. Andrews University 'ISHR' Research on South Pembrokeshire Flemings.

(Ms Amy Eberlin, St.Andrews, & Ms Pamela Hunt-contributor, Scotland & Wales and the Flemish People)

St Andrews' Institute of Scottish Historical Research.St. Andrews website

|

|

Writer thanks the wonderful work of Institute's members and most kind collaborator of 2ndMay 2015.

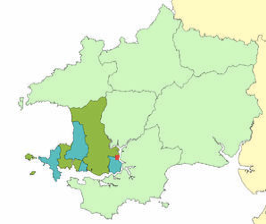

Pembroke, Rhos/Roose (Hundred), Haverfordwest & Landsker'Language'Line, Roch Castle

The Norman Hundred of Rhos/Roose and Roch Castle (Hotel) , built on rock out-crop by de la Roche family.

The Hundred Rhos/Roose, dark Green & Blue Manor of the FitzGodeberts ( Flemish) = de la Roches (Norman).

The Lordship of Haverford in dark Green. The family was also known as the 'de Rupe' family (Latin).

The Lordship of Walwyn's Castle in Blue. Both surname aliases were adoptions of NormanFrench style.

The Village of Llangwn (Laugharne) in Red. Middle: Landsker Line, Pembrokeshire/South Dyfed in Wales.

"The Flemings of Pembrokeshire"(Amy Eberlin, ISHR, St Andrews)

A web posting by Pamela Hunt [resident of the Village of Llangwm (aka Laugharne), a local historian and also a very active

Antiquary], examines why the Flemings had come to Wales and describes an

ambitious project that seeks to restore an old Flemish church, and gain a

better understanding of Flemish footprint in Pembrokeshire.

In one extract of William of Malmesbury's "Chronicle of the Kings" written

in 1125, there is a passage that caught the eye of the Pembrokeshire

village of Llangwm's Local History Society:

"The Welsh, perpetually rebelling, were subjugated by the king (Henry 1 1100-1135) in repeated expeditions, who, relying on a prudent expedient to quell their tumults, transported thither all the Flemings then resident in England. For that country contained such numbers of these people, who, in the time of his father, had come over from national relationship to his mother, that, from their numbers, they appeared burdensome to the kingdom. In consequence he settled them, with all their property and connexions, at Ross (dark green in the Pembrokeshire-South Dyfed graphic above) , a Welsh province, as in a common receptacle, both for the purpose of cleansing the kingdom, and repressing the brutal temerity of the enemy".

The village of Llangwm is in that Province (old pre-Norman 'Cantred' division) of Rhos and sits on the banks of the Cleddau Estuary. It is known to have been a winter haven for the Vikings who would draw their ships up onto the foreshores for repairs during the 10th and early 11 th century. They called the place Langheim, loosely meaning Long Street or Long Way. Many Vikings settled in this part of the world, indeed the parish to the north is called Freystrop, a derivation of 'Freya's Thorpe'. Freya is the Norse Goddess of Love and Thorpe is a village or hamlet. There are many communities in South Pembrokeshire that have Viking names. This is the area referred to by William where England's Flemings were sent to help the Normans keep order.

William of Normandy's marriage to Matilda, Princess of Flanders, meant that the Flemish became allies to the Normans and indeed Flemish nobles joined the 1066 expedition to invade England. With the success of the invasion some Flemish knights were given land and estates in England. When Henry I became king in 1100 he perceived a troubling superfluity of Flemings (probably disbanded mercenaries and others)2. So with one stroke Henry solved two problems. He sent the Flemings to Pembrokeshire with promises of land there. But more importantly they could help to keep order. As William of Malmesbury attests, the Welsh were constantly rebelling. It is believed that as many as 2,500 Flemings were sent to Pembrokeshire.

This wasn't the only migration to Pembrokeshire during Henry's reign, it seems there was another. According to the Welsh Chronicle of the Princes, or the ' Brut y Tywysogion' written around 1350, it refers to 'An inundation across the sea of the Britons ( English Channel ), flooding vast areas of Flanders wetlands'3. It goes on to suggest that this was a reason for there being Flemings in Pembrokeshire. But it doesn't tell us when during Henry's reign this happened. Professor Tim Soens of the University of Antwerp specialises in the history of Flanders Hydrography and he confirmed that there was a massive storm surge in October 1134 causing dozens of Wetland villages to be washed away and thousands killed. Was it out of kindness or a determination to reinforce his hold on South Pembrokeshire that Henry chose to invite the survivors of that catastrophe to settle in Pembrokeshire?

2.3/ Appendix: Pre-Invasion Flemings in Pembrokeshire (St. Andrews Univ.)

The Pre-Invasion Flemings in Pembrokeshire

The ancient administrative centres of Modern Pembrokeshire/South Dyfed are illustrated below.

Small -to- Large castles: Earthwork Castles & Stone Castles, Roch Castle (north-west of Haverfordwest)

Small -to- Large discs : Marcher Boroughs & Chartered Boroughs

The Normans established a Cordon Sanitaire with a string of castles that stretched from Newgale in the west to Laugharne (Llangwn) in the east. This became known as the Landsker Line. Those Welsh who refused to accept Norman rule were forcibly moved north. Up until the end of the 19th century, the area to the north was referred to as 'The Welshry' and they would refer to the south as 'Down Below'. Even today, journey a mile or so north of the Landsker and you will find Welsh being spoken, but it will be hard to hear Welsh spoken to the south of the Landsker.

In an article written by the Methodist Minister posted to Llangwm in 1864, he described the people of Llangwm as Hardy fishermen and women. He went on:

"The customs that prevail in this community are peculiar. Separate and

distinct from the Welsh race, they claim descent from the Flemings who

landed at Milford and took possession of that town and also of

Haverford and possessed themselves of the surrounding country in the

reign of Henry 1.

From that time to this, they have retained their distinctive character.

You need not ask them the question so often asked in the north of the

Principality 'Fedrwch chivi siared Saesneg?' (Can you speak English?)

As all of them are essentially English, so far as their language is

concerned. These people, though now for the most part on a level with

their Welsh neighbours have retained for them, and their language, a

hereditary contempt".

He goes on to write that they will have nothing to do with those who live in the Welshry. He noted too that the women, having chosen their husband rather than the other way round, would then retain their maiden name after marriage, something that still occurs in the Flemish speaking areas of Belgium and Holland today. Those 19th century people of Llangwm, still boasting pride in their Flemish ancestry used also to refer to the 'Dolly Roach' family being lords of the manor during medieval times. They were referring to the De La Roche family who had lands both at Llangwm and further north at Roch. That is when Godebertus Flandrensis became a person of considerable interest. It turns out that he was the 'patriarch' of the dynasty that became the De la Roches. Very little record of him survives and one of the goals of the project is to find out exactly who he was.

There are many places 'below the Landsker' that can claim a strong Flemish past: Tenby, Flemingston, Wiston, Walwyn West and Tancredston for instance. But it's Llangwm, in spite of the village's Welsh name, which seems to retain one of the strongest links with its medieval Flemish past. And what of that name? It's only the thirteenth name by which this community has been called since the Vikings came! Other names dating from 1200 include Landegunnie, Landigan, Langham, Langomme and Langum, but barely 30 years after that Methodist Minister wrote his piece, a Welsh speaking Rector appointed to St. Jerome's Church decided that Langum, the name the village had been known since the 1600s, was a distortion of the Welsh Llan Cwm, meaning Church in the Valley. So the village's name was changed once more.

[ This had for centuries been a remote and insular village and marriages outside the community were discouraged. Many of those residents wouldn't have even ventured as far as Haverfordwest, except of course the Hardy Langum Fisherwomen who would carry baskets of herring, mussels, cockles and oysters to sell at the market there as well as at markets in Tenby and further afield. Llangwm's Flemish past had largely been forgotten until quite recently. The urgent need for major repairs to Llangwm's Church of St. Jerome unexpectedly provided a special opportunity to rediscover those roots. St. Jerome's had been built by Flemish craftsmen around 1185, but in recent years the fabric of the building began to deteriorate quickly. In 2013 a bid to Heritage Lottery for development funding for a project that would combine the repairs and renovations with research and an exhibition was successful. That development led to a full second stage bid a year later and that has been successful too. The project is expected to commence in July 2015 . ]

The primary aim is to discover as much as possible about Godebertus Flandrensis and his descendants , who changed the surname two generations on to De la Roche. Another goal is to find out when the family settled in the area and to discover more about the church and how it has changed over the years. Then with all that information gathered it is hoped to create an exhibition in the North transept of the church with a locally designed and sewn tapestry. Modern communications techniques will be used to tell the story. This funding will allow researchers to visit the National Archive at Kew, the British Library and other sources of written research material and spend time checking out writings related to the De la Roche family, and the village. The funding will also support archaeological research at the site of a medieval manor house at the edge of the village, which may also have secrets to share. In addition there will be funds that will allow six male volunteers, who can confirm that their families have lived in this area for at least 250 years and the male line of that family is unbroken, to have their DNA tested, hopefully to discover they have Flemish Ancestry.

The project will be a significant challenge. It could be described as a 500-piece jigsaw that has, perhaps, 300 pieces missing. The objective is to find as many of those missing pieces as possible.

Below is a list of issues that it is hoped the research will shed light

on: (author of this presentation)

1. We know that Godebert was born in 1096, ten years before Henry 1

sent the Flemings out of England. Most genealogy sites suggest he was

born in Pembroke, but one states Flanders. If he was born in Pembroke

that suggests that his father took part in that initial invasion of

South Wales in 1087. Yet it is known that the Normans looked down on

the Flemings. As a result, the Flemings were eager to adopt Norman

lifestyles and to be seen to be more like them; this is the reason that

Godebert's grandsons adopted the De la Roche surname. If his father was

part of that invasion, who was he? And what was so special about him

that the Normans allowed him to join that invasion?

[Godebert's and their kin and many Flemings were 'professional

mercenaries'. They were a big part of the Irish Invasion too, 1167 -

1171]

2. Godebert named his sons Richard and Robert, the same names as the

younger brothers of Mathilda Princess of Flanders. Was he possibly a

relation of the ruling family of Flanders?

[Unlikely, the FitzGodeberts looked up to the Prendergasts, who looked

to Strongbow]

3. Who was the first of that family to settle in Llangwm? The 12 th century dovecote at Great Nash Farm and the site of the

medieval manor house suggests that it must be one of the first three

generations - Godebert, his sons Richard or Robert, or indeed Robert's

eldest son David De la Roche. Richard died with no heirs.

[mmm?, Robert's sons, David, Henry &Adam, … Richard's sons, William,

Henry & Adam, probably!]

4. Yet in "The Greatest Knight", the biography of William Marshall, the

author Paul Asbridge refers to this particular David De la Roche

betraying William Marshall over lands in Leinster. If David lived in

Leinster at that time, then who was living in Llangwm?

[There was a De la Roche family disagreement over lands in Fernegenal,

Wexford (granted to Richard FitzGodebert directly by Strongbow,

Richard FitzGod died, Raymond deRupe inherited, & died. Gerald

deRupe seized the lands to family discontent, and passed half to D.

Sinad]

5. Why indeed did that family create an estate in Llangwm? It is four

miles south of the Landsker Line. Surely the lands that were granted to

the Flemish nobles would have been closer to the defensive line and it

is known that Adam, Robert's youngest son completed Roch Castle in the

1180s. So when was the Llangwm estate occupied and by whom? The first

recorded De la Roche presence is David Lord of Landegunnie and

Maenclochog in 1244.

[Rhos was their homeland, and Llangwm is well sited. The family were

busy in Ireland after 1180]

6. The De la Roche's were active in the conquest of Ireland. The Norman

French poem, "The Song of Dermot The Earl" refers to Godebert's eldest

son Richard going to Ireland to help Dermot regain his lands with his

small private army two years before Strongbow's invasion. He failed

that time and was back in 1169 with Strongbow's force. He then died,

reportedly in Wexford, with no male heir in Ireland, enabling his lands

to pass to Robert's sons. So who had what

[Gerald deRupe passed half of the seized Fernegenal lands in Wexford to

D. Sinad. Ed.]

[Pamela, my thanks and my kindest regards, I so enjoyed your wonderful post. Ed. ( an Hiberno-Cambro-Norman-Flemish-Roman-Illyrian) ]

7. It is also known that the Flemish nobles Wizo and Tancred went to

Scotland to establish Flemish communities. Did they return to

Pembrokeshire? When?

[Would it therefore be the case of there being Caledonian-Cambro-Norman-Flemish-Roman-Illyrians in Scotsland?]

8. There is also a suggestion that Godebert too went to Scotland, but we

can find no evidence of this trip. Anyway the 1130 Court of Rolls [Henry I

] states that he was awarded lands in Pembrokeshire on a payment of 126

shillings. He is reported to have died in 1131 at the age of 35. So

when could he have undertaken what would have been a very long trip?

[Unlikely, he had already left many footsteps in the sand]

[Pamela Hunt, May 2015, Author of above note on Pembroke Flemings for St Andrews blog, Institute ISFR].

Biographical Note:

[

Pam Hunt chairs the Heritage Llangwm working group and has been

responsible for raising most of the £420,000 needed to complete

this project. She retired to Llangwm in 2006, having spent her

working life in broadcasting and television production, joining the

BBC as sound effects technician on The Archers in 1968. She left

the BBC in 1990 and started her own television production company,

producing documentaries usually with a history slant until her

retirement. She was intrigued by the fact that Llangwm's church had

two effigies and some intricate Norman carvings in what appeared to

be little more than a rural Victorian church.

]

Bibliographical Note:

The 4 main sources referenced as a Bibliography for this posted text

are appended at end of 5.6/. There are also a number of other posts on the topic of Flanders and

Flemings in Wales &Scotland.

2.4/ The Norman Invasion of Ireland, Timescale and Leadership

Timescale of Cambro-Norman-Flemish Invasion of Wexford, Waterford, Leinster & Ireland, between May 1167 and October 1171:

1166: Leinster, King Dermot McMurrough of Leinster deposed, [Dermot visited Bristol, Anjou (France) and South Wales].

1167: Wexford/Ferns, Reconnaissance, King Dermot, Richard (& Rodebert) FitzGodebert (aka de Rupe or de la Roche), 30 men.

1169: Wexford/Bannow, Maurice FitzGerald, Maurice dePrendergast, Robert FitzStephen & Robert deBarri (Barry), w.400.

1170: Wexford/Baginbun, Invasion leader, Raymond le Gross (Fitzwilliam) FitzGerald, 200 knights, archers, men at arms.

1170: Waterford/Passage, Richard FitzGilbert de Clare (aka 'Strongbow'), c.3,000 knights and men at arms, and including, Miles de Cogan, Meyler and Robert FitzHenry, Philip de Barri, Hervé de Montemarisco (Montmorency), and Hugh de Lacy.

1171: Waterford, King Henry II, Anglo-Norman Invasion, Sept. 1171-April 1172, c. 400 knights, 4000 men, Dublin, Wexford.

Leadership of Cambro-Norman-Flemish Invasion of Wexford, Leinster & Ireland, ex 1167

The Invasion could be described as a family affair. The majority of the leaders commonly identified and many of Strongbow's knights (those later acknowledged as having disembarked for invasion) were strongly inter-related. The extent of familial relations among the force is illustrated below, with the listings of known Knights separately after. The important but deceased Princess Nesta's family (she deceased by 1169) and Strongbow's personal allies lay at the centre of this extended family web. It even included some FitzRoy (Royal) cousins of Henry II. The post-facto listings of dis-embarkation do include a few likely Flemish names, those of Maurice and Philip de Prendergast, the FitzGodoberts (incl. de Rupe), the Flemings and possibly also de Hofe and de Herloter. There were no individual 'Sennetts' listed amongst accepted compilations of the participants. However, the surname is often listed among those family names whose origins go back to the period (see later Chapter 2.5/). Claims have been made for individual Sennetts, this is unclear or not quite fully proven to date.

Flemish 'Town Infantry' of mid 12th Century (below):

The Brabançons of Brabant, Belgium: Le Confrérie de St Sebastien (Brabantian Butchers Guild)

2.4/ Princess Nesta of Wales & FitzGerald, FitzStephen and FitzRoy(FitzHenry) Family Links

Nesta married firstly Gerald of Windsor. There were 3 fathers to just 5 of her male children among her family of 10 children in total (all her children survived), 1st spouse, Gerald FitzWalter de Windsor of Pembroke, (and Walter de Windsor having been a son of Odo or Otho of Normandy), 2nd spouse, Stephen de Castellan (Stephen of Cardigan), and the Princess earlier in her adolescent life having been also a consort of King Henry I.

The descendant chart below shows the relationship of Robert FitzStephen, leader of the 2nd landing; Maurice FitzGerald, another leader of the 2nd landing; and Raymond (FitzWilliam) FitzGerald le Gros, leader of the 3rd landing. The Raymond FitzGerald le Gross landing force was the last before Strongbow himself arrived. Robert and Maurice were half-brothers (through their mother Nesta), Raymond was nephew of both.

Robert FitzStephen had the following relatives who were involved in the Invasion: his son Ralfe; his 5 half-nephews Raymond FitzWilliam (le Gros) FitzGerald, Griffin FitzWilliam FitzGerald, Robert de Barri, Meyler FitzHenry and Miles Menevensis and half-brother Maurice FitzGerald. Robert FitzStephen and the older FitzGeralds were half-brothers to Henry FitzHenry (deceased before the invasion), who in turn had been an uncle to King Henry II.

Maurice FitzGerald married Alice de Montgomery. They had the following children: Gerald (Baron of Offaly), Walter and Alexander (Invaders), William (1st Baron of Naas), Maurice (of Kiltrany, Mayo branch, aka FitzMaurice or MacMorris), and Thomas, Robert and Nesta FitzGerald.

Maurice's son Gerald married Eve de Bermingham, a close relative of Robert de Bermingham who was one of the invaders. Another of Maurice's sons William FitzMaurice Fitzgerald, 1st Baron of Naas, married one of Strongbow's daughters, Alina de Clare. Their line included son William, and grandson David who married Maud de Lacy to carry on the Baronage of Naas. Maurice's daughter Nesta Fitzgerald married Harvey de Mont Marensi [aka Hervey de Montmorency], an uncle of Strongbow. Maurice FitzGerald's sister, Anagreta (Angharad] married William de Barri. Their children included Giraldus Cambrensis who chronicled the invasion, Philip de Barri who received large estates in Cork, and Robert de Barri, a grandson who also invaded Ireland. The de Cogans were half-brothers to the de Barri's.

Raymond (FitzWilliam) le Gros FitzGerald married Basilea de Clare, a sister to Strongbow. After Raymond's death (1186-89), Geoffrey FitzRobert (a possible son of Robert FitzStephen), married Basilea. Finally, Meiler FitzHenry's sister Meilerine (poss. aka Annabel) m. Walter de Riddellsford (Ridelsford/Ridensford). He is listed as Gualter de Ridensford in some histories.

Nesta's 1st spouse Gerald FitzWalter of Pembroke, 2nd spouse Stephen of Cardigan, &Henry I

| Stephen, Constable of Cardigan | Gerald FitzWalter de Windsor of Pembroke | King Henry I (Plantagenet d.1135 |

| | | | | | |

| Robert FitzStephen* (d. 1182 |

Maurice FitzGerald* (d. 1176) David FitzGerald (Bishop of St. Davids, d. 1177) William FitzGerald (d. 1173) Angharad FitzGerald (m. de Barri) |

William Adelin (Royalheir, d.1120) Empress Matilda/Maude (d.1167) (9 illegitimate male children, Henry b. 1105) (2xRobs,2xWills,Richard,Reginld,Fulk,Gilbrt) Henry FitzRoy/FitzHenry (d.1157/8) |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

Meredith FitzRobertFitzStephen Ralfe FitzRobertFitzStphen(d.1182) William Walensis (half-brother) [Geoffrey FitzRobert FitzStephen?] |

William FitzMaurice FitzGerald (Barons of Naas) Odo (FitzWilliam) FitzGerald (Carew, Lords Idrone) Raymond (FitzWilliam) FitzGerald*(Lords Carew) Gerald FitzMaurice FitzGerald (Earls Kildare) Thomas FitzMaurice FitzGerald (Earls Desmond) |

Meyler FitzHenry (d. 1216) Robert FitzHenry Annabel (m. de Ridensford ) |

source: http://www.britannia.com/history/docs/giraldus.html

Listing of Irish Invasion participants, as taken from Camden's Brittania Manuscript '1610:

Original source 2015: http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com , (this source not active of late re this page's info). List of persons who participated in Irish invasion project with Richard FitzGilbert de Clare 'Strongbow'.

Robert FitzStephen*

Harvey de Mont Marisco (Mariscis/Montmorency)

Maurice de Prendergast*

Robert Barri/Barry

Meiler FitzHenry

Maurice FitzGerald*

Redmond/Raymond*FitzGerald (neph. FitzStephen)

William Ferrand

Miles de Cogan

Gualter (Walter) de Ridensford/Riddellsford

Gualter (Walter), son of Maurice FitzGerald

Alexander, son of Maurice FitzGerald

Griffin, nephew of FitzStephen

William Notte

Robert FitzBernard

Hugh Lacy

William FitzAldelm

William Macarell

Hemphrey Bohun

Hugh De Gundevill

Philip de Hasting

Hugh Tirell

David Walsh

Robert Poer

Osbert de Herloter

William de Bendenges

Adam de Gernez

Philip de Breos

Raulfe FitzStephen

Walter de Barri/Barry

Philip Walsh

Adam de Hereford

John d’Courcy

Hugh Cantilon

Redmund FitzHugh

Miles (of St. David's) Menevensis w. FitzStephen

Walynus, a Welshman w. Maurice Fitzgerald

Gilbert d'Angulo (possibly de Angle/English?) w. Strongbow

Jocelyn d’Angulo (son) w. Strongbow

Hostilo (Costello) d’Angulo (son) w. Strongbow

Sir Robert Marmion w. Strongbow 1172

William de Wall w. Strongbow

Randolph FitzRalph w. FitzStephen

Alice of Abervenny w. Le Gros

Richard de Cogan w. Strongbow

Phillipe le Hore w. Strongbow

Theobald FitzWalter w. Henry II

Robert de Bermingham w. Strongbow

d'Evreux w. Strongbow

Eustace

Roger de Gernon w. Strongbow

de la Chapelle (Supple) w. Strongbow

End.

Camden’s Brittania Manuscript ’1610 (poss also 1695).

Camden’s Brittania had 6 editions ex 1586, for 200 yrs

From the work "History and Antiquities of the City of Dublin", by Walter Harris, Esq., an alphabetical list composed 1766 of "Norman/English adventurers as arrived in Ireland during first 16 yrs of Norman invasion".

"The History and Antiquities of the City of Dublin from the earliest accounts" 1766, Walter Harris, Listing

Barry (Robert, jun.)

Barry (Philip) neph. Robert Fitz-Stephen

Barry (Walter de)

Barry (Gerald) neph. Robert Fitz-Stephen

Basilia, sister to Earl Strongbow.

Bendeger (William)

Bermingham (Robert de)

Bevin (de) by some as Beuin.

Bigaret (Robert, maybe also aka Bigod)

Bluett (Walter)

Bohune (Humphrey de)

Borard (Gilbert de)

Borard (Robert de)

Braos (William de)

Bruse or Braos (Philip de)

Camerarius (Adam or Chamberlain)

Caunteton or Kantune (Reymond de)

Chappel (Richard de la)

Clahul (John de)

Clavill (John)

Cogan (Miles de)

Cogan (Richard de)

Comyn (John) Archbishop of Dublin.

Constantine (Geffry de)

Curfun (Vivian de)

Courcey (John de)

Cressy (Hugh de)

Curtenay (Reginald de)

Dullard (Adam)

Feipo (Adam de)

Ferrand (William)

Fitz-Aldelm (William)

Fitz-Almane(Walter, neph. Fitz-Aldelm)

Fitz-Bernard (Robert)

Fitz-David (Milo)

Fitz-Gerald (Maurice)

Fitz-Godobert (Richard)

Fitz-Godobert (Robert)

Fitz-Henry (Robert)

Fitz-Hugh (Reymund)

Fitz-Martin (Robert)

Fitz-Maurice (Alexander)

Fitz-Maurice (Gerald)

Fitz-Philip (Henry)

Fitz-Philip (Maurice)

Fitz-Ralph (Randulph)

Fitz-Richard (Robert)

Fitz-Stephen (Amere/Meredith,son)

Fitz-Stephen (Robert)

Fitz-Stephen (Ralph)